#Careers

#Careers

“Chaos will not swallow my humanity”

Family physician and pediatrician Mariana Sato explains how she manages to combine art, science, and medicine to humanize patient care in Brazil’s public health system

Mariana Sato: “It’s not just about taking care of the physical body, but of a body that exists in social, historical, and cultural dimensions” | Image: Marcelo Nishio

Mariana Sato: “It’s not just about taking care of the physical body, but of a body that exists in social, historical, and cultural dimensions” | Image: Marcelo Nishio

After noticing that her patients seemed uncomfortable, family physician and pediatrician Mariana Eri Sato Nishio transformed the small waiting room at the Basic Health Center (UBS) where she works on the western outskirts of São Paulo.

Together with her colleagues and members of the local community, Sato decided to change the space and make it more cheerful, with the aim of reducing stress among patients who sometimes have to wait hours to see a doctor.

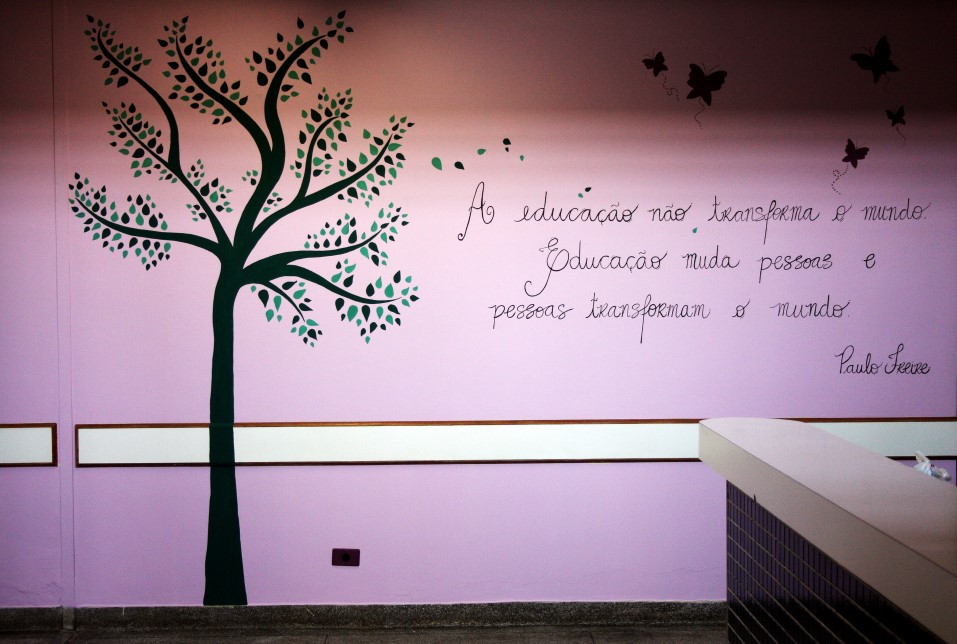

Simple alterations were made, such as painting the walls in bright colors with a stencil of a tree on one of them. “The environment has changed completely,” says Sato, who told the story at TEDxUSP, an event held at the School of Medicine of the University of São Paulo (FM-USP) at the end of May.

In her talk, the doctor spoke of her mission to prevent the dehumanization of medicine and science and her effort not to let “the chaos of day-to-day life swallow my humanity.”

By combining science, medicine, and art, Sato has managed to unite three worlds thought distant by many. She also realized that her interest in art could play a central role in her work as a doctor.

This interdisciplinary perspective has even influenced Sato in her academic career. During her master’s degree in preventive medicine at USP’s School of Medicine, she explored the relationship between health, art, and humanization. And during her doctorate, currently in the final stages at the USP School of Public Health, the physician is studying integrative and complementary health practices.

As supervisor of FM-USP’s Primary Care Program, Sato is striving to reconcile scientific methods and integrative medicine—an approach that reaffirms the importance of the relationship between the patient and the health professional.

Sato spoke to Science Arena about her journey in medicine, explaining how medicine can incorporate fewer formal biases without losing technical rigor.

Science Arena – How did the process of uniting art and medicine occur?

Mariana Sato – It happened organically. Medicine is often seen as a harder, more objective, concrete, technical, and protocol-based science. But the creative perspective has always interested me. How can someone intend to care for human beings without making use of humanistic elements?

To me, it has always seemed very illogical to ignore knowledge from other fields, such as anthropology, history, sociology, and philosophy, which seek to understand humans in a historical and social context.

It’s not just about taking care of the physical body, but of a body that exists in social, historical, and cultural dimensions.

It is important to highlight that there is more to art than the classic forms of expression people normally think of, such as painting, music, cinema, and theater.

Art is any means of creative expression—a dialogical and spontaneous construction that happens between people. Art can thus be present in medicine.

Does that apply to any branch of medicine?

This broader concept of art, of collective construction, can easily be utilized within medicine, which involves both technique and art. The technique is the protocol, the guideline, which cannot be applied indiscriminately.

That’s where art comes in—when a patient meets a doctor, the phenomenon of collaborative construction occurs through the development of a care plan based on the patient’s background, circumstances, and what they say.

This is an artisanal process that involves interpersonal exchanges and being open to new things. If we think of art as this creative process of collaborative construction, it can be used in medical consultations of any specialty.

Can it influence the way people see doctors?

What I’m proposing is that we can be very professional and very technical, but through a slightly more organic and spontaneous relationship within the consultation.

We have to use all of our technical knowledge to make diagnoses and suggest treatment options, but we also need to be open to new things, allowing for more spontaneous interactions between the people, behind the roles they play. Through this dynamic, a much more effective care plan can be drawn up.

How did this “union” begin in your career?

I realized that much of what patients talked about at their consultations were problems that could not be completely resolved through the pharmacological use of medicine.

In consultations, in addition to applying the conventional approach and improving communication, I began to understand that forms of art could also play an important role in the therapeutic process.

Of course, we need to adapt to the reality of how a medical consultation occurs, but there is room to let our own humanity and our own creativity shine through.

Did you ever suffer prejudice for using these less conventional approaches?

I have many colleagues, each with their own point of view on what medicine should offer. At USP’s School of Medicine, I thought I might face some kind of more explicit opposition, but I never did.

Being who I am at an institution like this [the university] is in and of itself a form of resistance. And I think it’s interesting, because I represent a type of doctor that is different from the other hegemonic types at the institution. This could inspire some people, and at the same time it might displease others.

And at Basic Health Centers?

I have always had a very good connection with the community and with my patients, and I have never experienced any kind of confrontation. Health professionals working in primary care are generally more open to adopting popular knowledge and the wisdom of the community.

They are usually doctors who have chosen to work outside hospitals to be closer to the community. My perception is that they are professionals with a more flexible profile.

Changes made by pediatrician Mariana Sato, in partnership with patients and health professionals, to the waiting room of a health center in western São Paulo | Images: Archive/Mariana Sato

And they are therefore more open to interventions like the painting session you hosted at a health center waiting room in São Paulo?

The waiting room has always been a place where people feel very stressed and impatient, generally carrying a lot of anxiety. In an attempt to improve the atmosphere—since hiring more healthcare workers to speed up service was not feasible—I encouraged my fellow professionals and the community to help empower the space.

We suggested a new layout so that the environment would not be just somewhere instrumental, hygienic, and functional. Health services typically have more “sterile” features.

With the support of the manager, Ana Emília, who herself takes a more progressive view of healthcare, we designed the new space with people actively participating in the creative process through drawings, voting, planning, and ultimately implementing the changes.

How was this all made possible?

It is important to say this, because anyone who visits a Basic Health Center will notice that they are standardized spaces, with the same colors, the same designs—everything is very similar.

We were able to overcome this and propose another approach with the support of the management council, an entity that represents both the community and healthcare professionals.

This council approved our plan to renovate the waiting room, and it was thus possible to justify the changes to the municipal administrators.

It’s great, because this participatory management process is part of the SUS [Brazil’s public health system] and without these different levels of authority, initiatives anchored in art like the one we carried out would not have been approved or executed.

How can we reconcile medical technique and humanist care?

Being an excellent technical professional is a prerequisite. But that alone isn’t enough to be a good doctor; you also need experience as a person, to have a much broader background than just medicine. This means drawing from other influences, such as art, cinema, theater, literature, meeting different kinds of people, experiencing “otherness.”

We need to step out of our own bubbles and put ourselves out there—our field of knowledge is life, and that includes lives that are different from our own.

We will come across all kinds of people. Our repertoire therefore has to encompass other dimensions, other perspectives, and other ways of life. Otherwise, it is impossible for us to truly understand and help those seeking us out.

How important is communication in this process?

Communication is very important, and it can be developed through technique. Good doctors not only know medicine; they also know how to communicate. However, in addition to communication skills, doctors also need to develop a legitimate disposition towards the person to whom they are speaking.

That’s why I say that part of a doctor’s training takes place outside of themselves, and I ask my students to constantly exercise a sense of otherness and to continuously make efforts to leave their bubble. I often tell them that they shouldn’t feel guilty about going to the cinema or the theater in their rare moments of free time. It’s part of their training.

Is family and community medicine on the rise in Brazil?

It’s a very important field, and in Brazil it has only recently begun gaining momentum. In other countries, such as England, it is already well established. There, the entire health system is built around primary care, with the prominent role of the family physician.

Here in Brazil, if a person has a headache, they have to make a pre-diagnosis in order to decide which specialist they need to see: the ophthalmologist if they think it’s a vision problem; the neurologist if they think it’s a migraine; etc.

Most of the time, a good family doctor will resolve the problem without having to refer the patient to other specialists, and without the need for expensive or complicated tests.

A family doctor can resolve a case simply by monitoring the patient over time, since most everyday health problems are self-resolving, temporary, and do not require more complex medical intervention.

And in the private system?

They are also realizing that investing in primary care is good for the patient and good for the system, from an economic point of view, since it does not require so many exams, hospital admissions, and medications. When you have a good team accompanying the family over time, this saves resources for the private system.

Any tips for anyone looking to move into this area?

An internship can be really helpful to learn what the life of a family physician is like, because there are many challenges. There are other specialties that provide greater financial rewards, but for some, the greater level of involvement in the community is a real source of satisfaction at work.

It can be highly rewarding to perform a role in which you see the impact you are having through people’s recognition—in some other specialties, you can get the feeling that being a doctor is not exactly how you imagined it.

*

This article may be republished online under the CC-BY-NC-ND Creative Commons license.

The text must not be edited and the author(s) and source (Science Arena) must be credited.