#Careers

#Careers

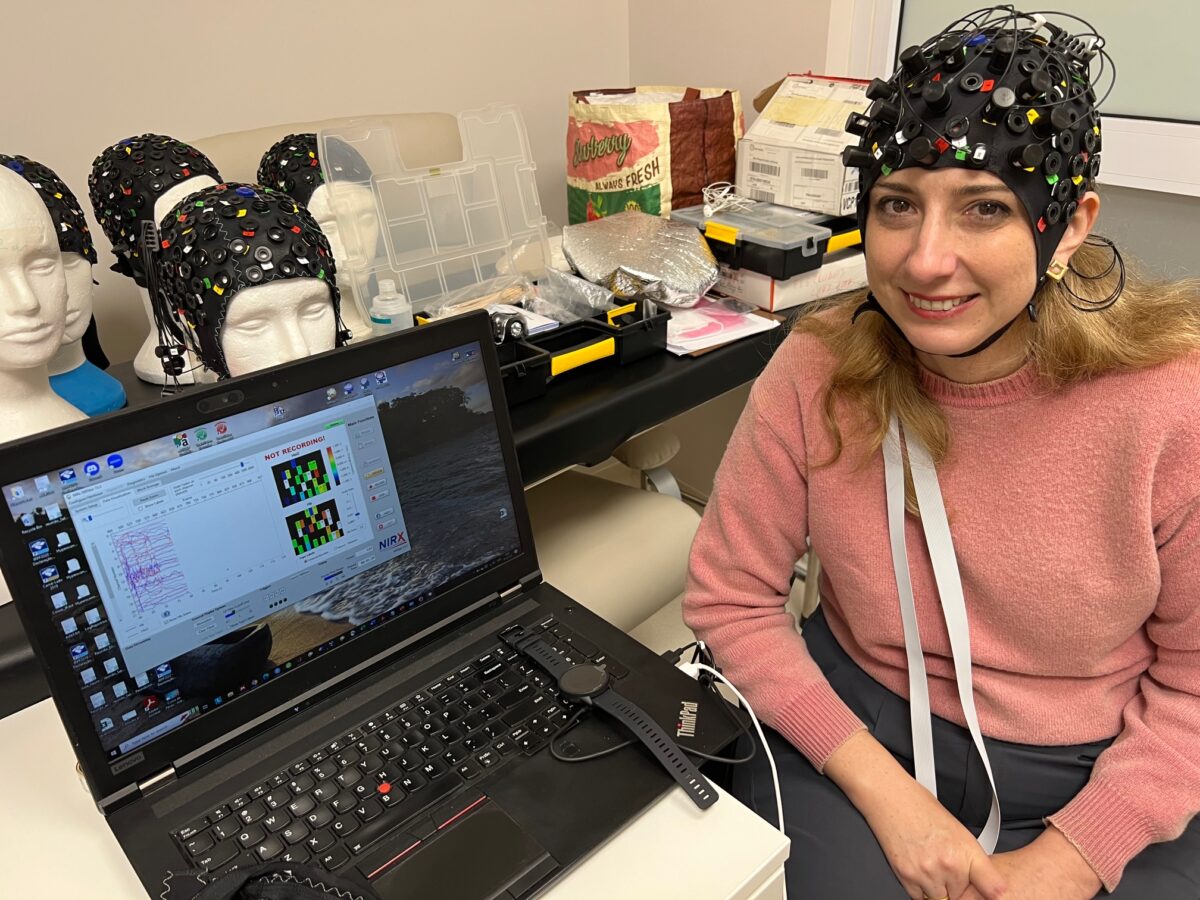

Eleonora Zioni: Designing architecture for better health

Known as “the design doctor,” Zioni combines architecture and neuroscience to improve the patient experience in hospitals

Architect and urban planner Eleonora Zioni has designed more than 200,000 square meters in hospitals and medical clinics to promote health and well-being in therapeutic spaces | Image: Anna Quast

Architect and urban planner Eleonora Zioni has designed more than 200,000 square meters in hospitals and medical clinics to promote health and well-being in therapeutic spaces | Image: Anna Quast

“Don’t let the university application exam define your life.” Those were the father’s words that guided the career of Eleonora Zioni, an architect and researcher, and as she was affectionately nicknamed by her students, the “design doctor.”

With a degree in architecture and urban planning from the University of São Paulo (USP), Zioni had an interest in the medical field even before her classes began—at one point undecided between studying medicine or architecture.

It was then that her father, an engineer, offered his advice, which was intended for a specific moment but she now recognizes as a broader principle.

“I believe it is very important for us to know what we truly want and not let exams or challenges dictate our path, because there are endless possibilities,” says Zioni, a postgraduate professor at Hospital Israelita Albert Einstein.

During her undergraduate studies, her curiosity was sparked by subjects such as urban planning, design, and art history. But medicine remained an underlying interest.

She took her first step towards reconciling these topics in her final thesis: hospital design.

“I was in the health field right from the start, and it is difficult because it involves a lot of engineering. In the 1990s, people were very reticent and did not want to get involved. They said that no one knew how to design a hospital,” she recalls.

Zioni continued in the field, spending 15 years working on hospital projects and coordination at the American multinational Albert Kahn Associates.

She has designed more than 232,000 square meters (m²) in hospitals, including units at Einstein Hospital. At Kahn, she learned to adapt methods from the automotive industry to the hospital context, such as the organization of production processes.

One of the therapeutic environments designed by Eleonora Zioni, opened in 2009, was the Morumbi unit of Hospital Israelita Albert Einstein in São Paulo. The space was created to make patients, visitors, and employees feel relaxed. A large sculpture of German physicist Albert Einstein (1879–1955) serves as an emotive focal point. The labyrinth outlined on the floor is an invitation to meditate outdoors, a chance for “the brain to shift its focus away from a person’s problems,” says Zioni. The garden provides a space where people can feel in touch with nature despite being in a man-made environment, based on the concept of biophilic design | Images: 1 and 2: Felipe Lampe; 3: Fábio H. Mendes/E6 Images

Quality of hospital environments

When Khan closed its office in Brazil, Zioni chose not to pursue an international career, instead returning to academia, enrolling at USP’s School of Architecture and Urbanism.

Her master’s degree focused on the quality of hospital environments, with an emphasis on intensive care units (ICUs), examining how sensory aspects—noise, smells, ergonomics, light, thermoacoustics, and visual comfort—influence the perception of space.

Her research established connections with environmental psychology, an area that studies how people’s perceptions and feelings are affected by their physical surroundings.

“Hospital architecture is full of rules, health regulations, and a lot of data—that is why people are afraid to get involved. But when you consider the more subjective approach of how a person feels, there is more opportunity to be creative,” says the researcher.

“Many people are afraid of hospitals or simply do not want to be there; changing that image has become my mission,” says Zioni.

This approach can be applied not only to hospitals, but also to clinics, doctor’s offices, and nursing homes. Seeking greater professional autonomy and the opportunity to link practice with research, she founded Asclépio Consultoria, named after the Greek philosopher Hippocrates Asclepiades (460–370 BC) and the ancient temples where people sought healing and well-being through medicine and contact with the environment.

Today, Zioni is one of Brazil’s most renowned names in hospital architecture. She created and led one of the country’s first postgraduate programs in the field, which was launched at Einstein in 2018 and has already been attended by more than 700 students.

She also edited the book Conhecendo a arquitetura hospitalar (Understanding hospital architecture; Manole Editora, 2022), one of the few up-to-date publications on the subject in Portuguese, with collaboration by renowned international professionals.

Neuroarchitecture: A frontier field

Her current research at Einstein focuses on neuroarchitecture, a field that links neuroscience and architecture to study how environmental stimuli affect human emotions and perceptions.

“When we hear a story, it moves us and leaves a lasting memory. I really like this humanizing aspect,” says Zioni.

“That is why I transitioned from architecture to neuroscience: architecture has always been about listening to people’s needs. I always knew that. But it has been a long road to get academia to appreciate it. I have been working in this field for 30 years.”

Zioni believes that maintaining a close connection to practice is essential, especially in a constantly changing field like architecture.

In her consultancy work, she analyzes circulation, thermal comfort, lighting, ergonomics, and other factors that directly impact user well-being.

Biophilic design, which aims to bridge the gap between nature and man-made environments, has become another key element of her work. “Sustainability is essential because we spend 90% of our lives in man-made environments and we need to feel at home in them, to bring nature closer.”

Science could contribute even more effectively to finding solutions to society’s problems if researchers were to put more stock in aspects such as creativity, sensitivity, and empathy, Zioni says.

She points out that thinking outside the box is increasingly what sets us apart from technologies like artificial intelligence. “The more creative, sensitive, and humanized we are, the more unique we become.”

Neuroarchitecture, she emphasizes, is one of the most promising fields for the coming decades, with the potential to address various mental health challenges. “Understanding the subjective needs of individuals and translating them into more empathetic environments is an essential step towards creating a better society.”

*

This article may be republished online under the CC-BY-NC-ND Creative Commons license.

The text must not be edited and the author(s) and source (Science Arena) must be credited.