#Columns

#Columns

Science diplomacy in an era of disruption

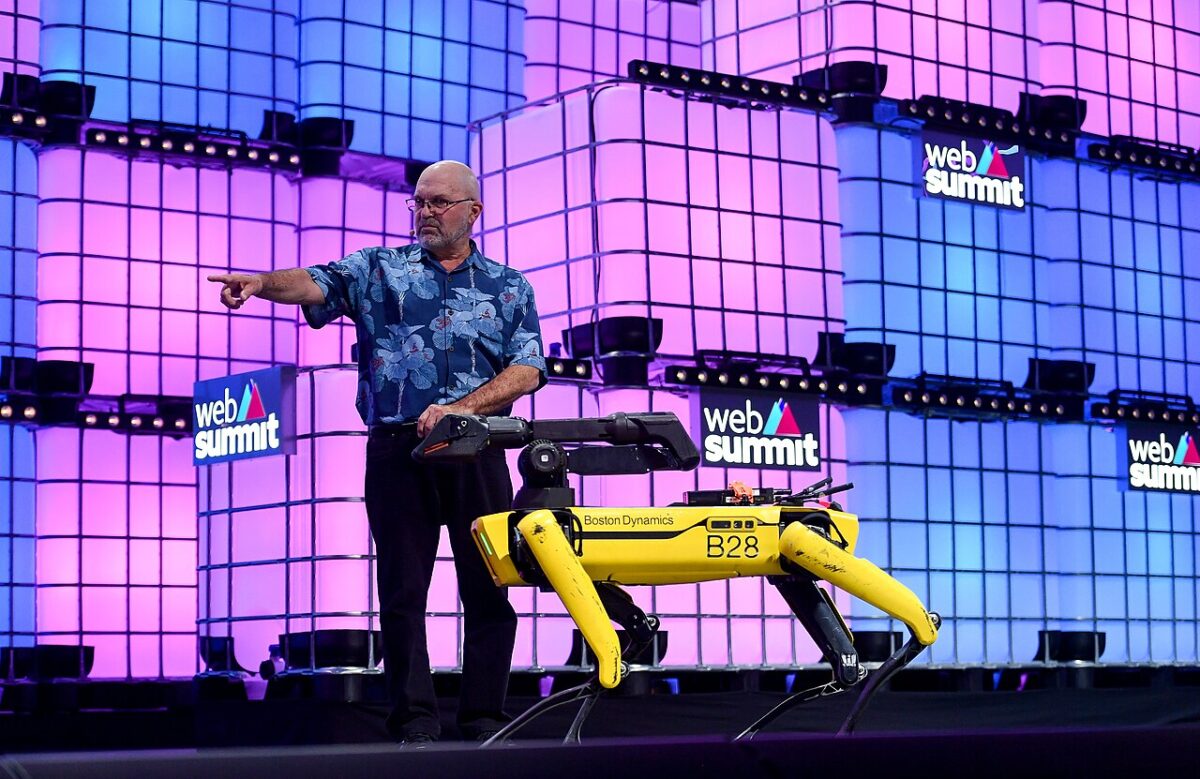

In the evolving geopolitical context, private companies act as supranational entities, shaping policies according to their corporate interests

Companies have become key players in the realm of science diplomacy, a space historically occupied solely by government representatives and academic scientists | Image: Hunter Scott / Unsplash

Companies have become key players in the realm of science diplomacy, a space historically occupied solely by government representatives and academic scientists | Image: Hunter Scott / Unsplash

In Latin American popular culture, turning 15 is typically a festive occasion. Rooted in significant pre-Columbian civilizations—where this milestone symbolized the passage into puberty—the celebration is known in Spanish-speaking countries as the quinceañera.

In stark contrast to the joyful tone usually associated with such milestones, the commemoration of the 15th anniversary of the publication New Frontiers in Science Diplomacy took place with little fanfare during the recent annual meeting of the American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS).

This esteemed organization is the older counterpart of our Brazilian Society for the Advancement of Science (SBPC)—a difference of precisely one hundred years.

The subdued nature of the commemoration was not due to a lack of merit. The joint publication by the AAAS and the British Royal Society has become a foundational reference for leveraging scientific knowledge in cooperative efforts to address challenges that no country is capable of resolving alone.

These include some of the most pressing issues of our time, affecting billions of people, such as restoring planetary health, ensuring food security, and safeguarding human dignity in the face of totalitarianism now amplified by emerging technologies.

In this context, as concerns grow over the problematic use of facial recognition systems, it is important to recall how advanced data tabulation and processing technologies once played a central role in enabling the Nazi regime’s atrocities.

The initial step was a national census, used as a tool to identify Jews (as defined by the National Socialist Party), Roma (referred to as gypsies), and other groups deemed undesirable by the regime.

The lucrative deals struck by the German government with the then global leader in this field also thrived in occupied European countries. The seemingly innocuous Hollerith technology—familiar to many through its later use in pay stubs—facilitated the ability of the forces of evil to locate and apprehend targeted populations en masse, thereby contributing to the technification of genocide.

Adverse context

The optimistic expectation, articulated in the introduction to the original 2010 document, envisioned science diplomacy as a means of “creating a new role for science in international policy-making and diplomacy… to place science at the heart of the international agenda for progress.” However, this vision has since encountered an increasingly unfavorable reality.

Indeed, just fifteen years later, “the geopolitical context is increasingly adverse, power is more widely distributed, and relations between the major powers have become more competitive,” as noted in Science Diplomacy in an Era of Disruption, a follow-up publication released at the aforementioned meeting, again co-published by the AAAS and the Royal Society.

Other disruptive elements include the rapid pace of technological advancement, particularly in the field of artificial intelligence, as well as the growing influence of non-state actors, including the so-called “titans of technology.”

These developments are straining the very foundations of constructive cooperation, the ideal that originally underpinned the convergence of science and diplomacy.

From a realistic perspective, the new framework underscores that science diplomacy is ultimately a tool used to advance the diplomatic objectives of a nation or organization, objectives that may be perceived as either positive or negative.

In this context, both overt and covert pressures—at times bordering on coercion—have increasingly emerged, often justified by alleged threats to national security in the realm of international scientific collaboration.

This heightened sensitivity to these risks affects not only global research cooperation but also the mobility of researchers and students from higher education institutions, particularly in scientific fields deemed sensitive.

Non-state diplomacy

The new document builds upon its predecessor by broadening the scope to include the use of diplomacy by non-state actors, especially in the corporate sphere. Companies are increasingly employing diplomatic strategies to advance their commercial interests, especially where technological innovation is at stake.

A small but growing number of private companies that command vast assets are operating as supranational entities, adjusting their national presences according to corporate interests.

The political influence of these “titans of technology” has become so significant that some now maintain permanent teams in cities that host major multilateral organizations, including New York, Paris, Geneva, Washington, and Brussels.

Conversely, nations have begun establishing diplomatic representations in “tech capitals,” particularly in Silicon Valley. They are also expanding science, technology, and innovation sections within existing diplomatic missions.

The increasingly global movement of data, coupled with the rapid expansion of digital platforms, has intensified clashes between differing societal value systems.

These tensions reflect contrasting national priorities: Europe emphasizes data protection, China focuses on controlling discourse that deviates from official narratives, and the United States champions freedom of expression.

Another major shift since the release of the original science diplomacy report 15 years ago is the rise of the private sector as a key funder of basic science and its applications across many countries.

Leading information technology firms now invest tens of billions of dollars annually in research and development, pushing the boundaries of knowledge in fields such as artificial intelligence and quantum technologies.

A striking outcome of this investment is reflected in the 2024 Nobel Prize in Chemistry, awarded to a trio of scientists—including two researchers from one of these tech giants. The third laureate, in keeping with tradition, is affiliated with a university.

The corporate researchers, based in a country that is not the corporation’s global headquarters, developed an artificial intelligence model capable of predicting the structure of nearly 200 million proteins. Since its release, the model has been used by more than two million people across 190 countries.

“Among a myriad of scientific applications, researchers can now better understand antibiotic resistance and create images of enzymes that can break down plastic,” stated the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences in its award announcement.

Innovation diplomacy

The phenomenon described here underscores how companies have become major players in the realm of science diplomacy, which is traditionally the domain of government representatives (diplomats) and academic scientists.

Anyone familiar with policy frameworks aimed at promoting science, technology, and innovation will recognize the emergence of the fruitful Triple Helix model.

There are, however, instances in which large corporations position themselves as operating on a level that transcends national governments, a dynamic that has been evident in recent controversies.

Developments in this evolving field have been closely followed by the São Paulo Innovation and Science Diplomacy School (InnSciD SP), an initiative launched in 2019 at the University of São Paulo (USP). It began as the São Paulo School of Advanced Science, supported by the São Paulo State Research Foundation (FAPESP).

In its founding year, the school introduced groundbreaking concepts and approaches, structured around two central pillars: science diplomacy and innovation diplomacy.

It also provided 100 young researchers, half Brazilian and half international, with access to major research infrastructures in the state of São Paulo.

Today, the school operates annually, alternating between virtual and in-person formats, always with the participation of strategic partners.

Each edition selects a pressing global issue to be examined through the lenses of science diplomacy and innovation, with input from both national and international experts and practitioners.

The most recent edition of InnSciD SP, held in 2024, was structured in two main segments:

- The first focused on reviewing the evolution of science and innovation diplomacy. Participants from the inaugural edition reflected on trends that—unsurprisingly—also appear in the newly released AAAS and Royal Society document.

- The second explored how artificial intelligence is reshaping the frontiers of science and innovation diplomacy. Discussions covered its implications for peace and security, as well as the global competition over semiconductors, widely known as the “chip war.”

From diplomatic, academic, and corporate perspectives, participants examined how Brazil and other similarly positioned nations can play a more active role in shaping international regulations and regimes that help mitigate technological asymmetries in an increasingly turbulent geopolitical landscape.

Guilherme Ary Plonski is a senior professor at the School of Economics, Administration, Accounting and Actuarial Science and at the Institute for Advanced Studies of the University of São Paulo (USP), where he previously served as director. He was managing director of the Technological Research Institute of the State of São Paulo (IPT), president of the National Association of Entities Promoting Innovative Enterprises (ANPROTEC), and scientific coordinator of USP’s Technology Policy and Management Center. A full member of the São Paulo State Academy of Sciences (ACIESP), he is an emeritus researcher at the National Council for Scientific and Technological Development (CNPq). He also serves on the Research and Innovation Committee of Hospital Israelita Albert Einstein and on the Board of Governors of the Technion – Israel Institute of Technology.

Portrait: Leonor Calasans / IEA-USP

The opinion articles do not necessarily reflect the views of Science Arena or Hospital Israelita Albert Einstein.

*

This article may be republished online under the CC-BY-NC-ND Creative Commons license.

The text must not be edited and the author(s) and source (Science Arena) must be credited.