#Essays

#Essays

Organ transplants in Brazil: The challenges

Science and the health system seek to improve the socially and financially costly donation/transplant process

With successful transplants resulting in decreased mortality and increased survival, the number of people on transplant lists has increased significantly, while many still do not have access to this form of treatment | Image: Shutterstock

With successful transplants resulting in decreased mortality and increased survival, the number of people on transplant lists has increased significantly, while many still do not have access to this form of treatment | Image: Shutterstock

In the last 40 years, the history of organ donation and transplantation has been marked by continuous advances and hurdles both worldwide and in Brazil. Over the years, many health professionals have dedicated themselves to identifying and developing safe and efficient care and management processes, with the aim of prolonging life and giving hope to those for whom a transplant is the last available treatment option.

But there can only be a transplant if there is a donor, and this indivisible binomial is what results in the relationship known as the donation/transplant process.

Donation and transplantation therapy first became a real possibility after Harvard Medical School’s ad hoc Committee published its definition of brain death in the late 1960s.

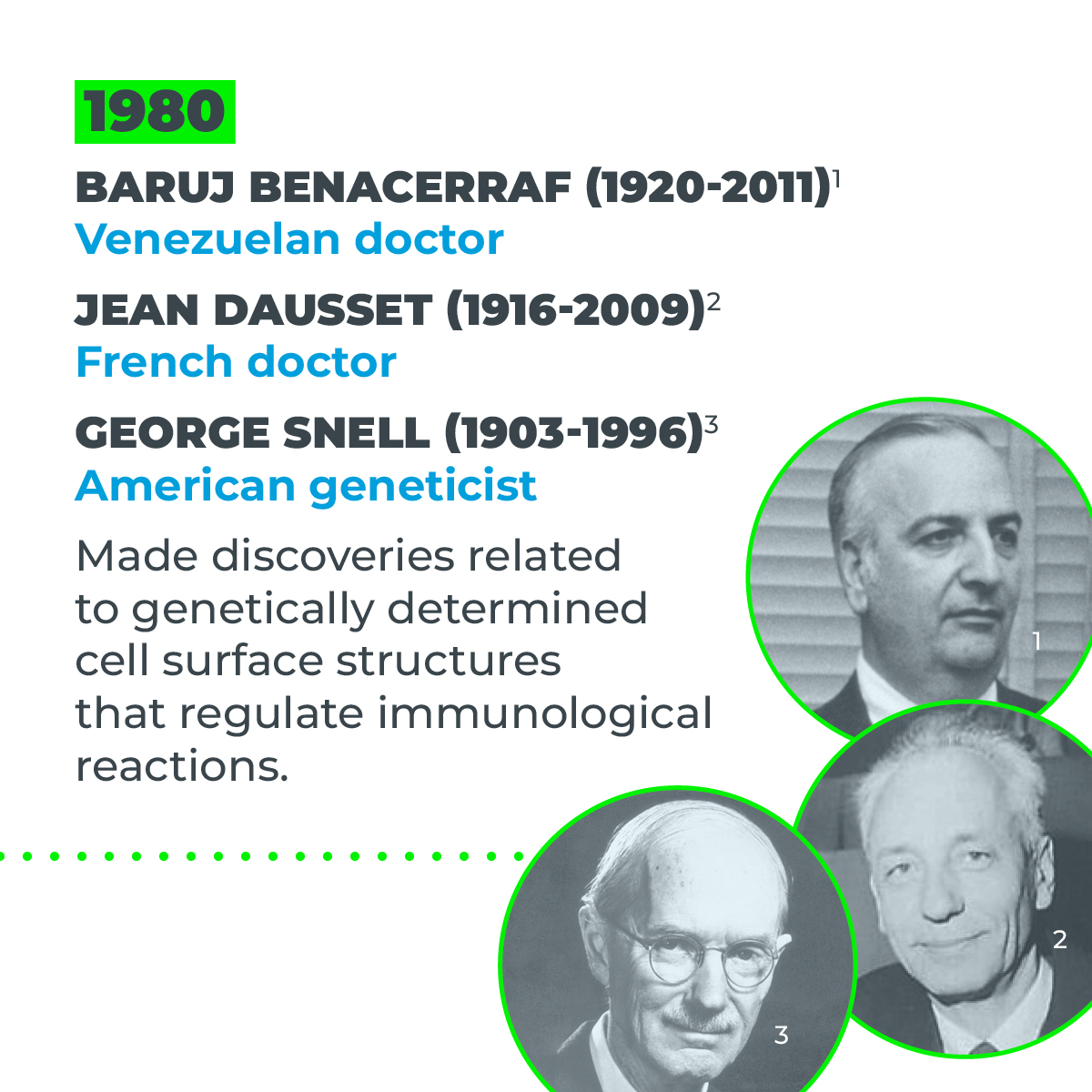

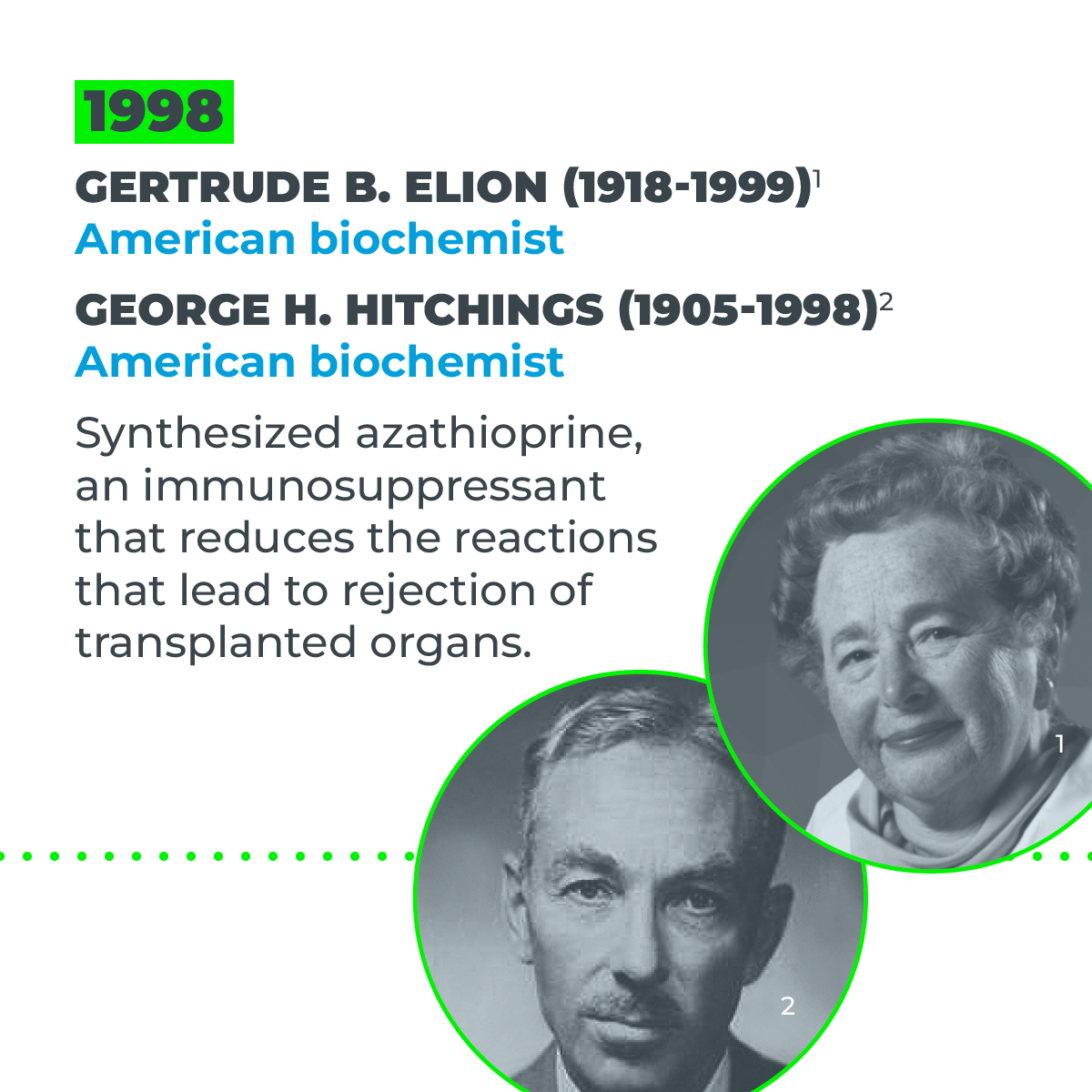

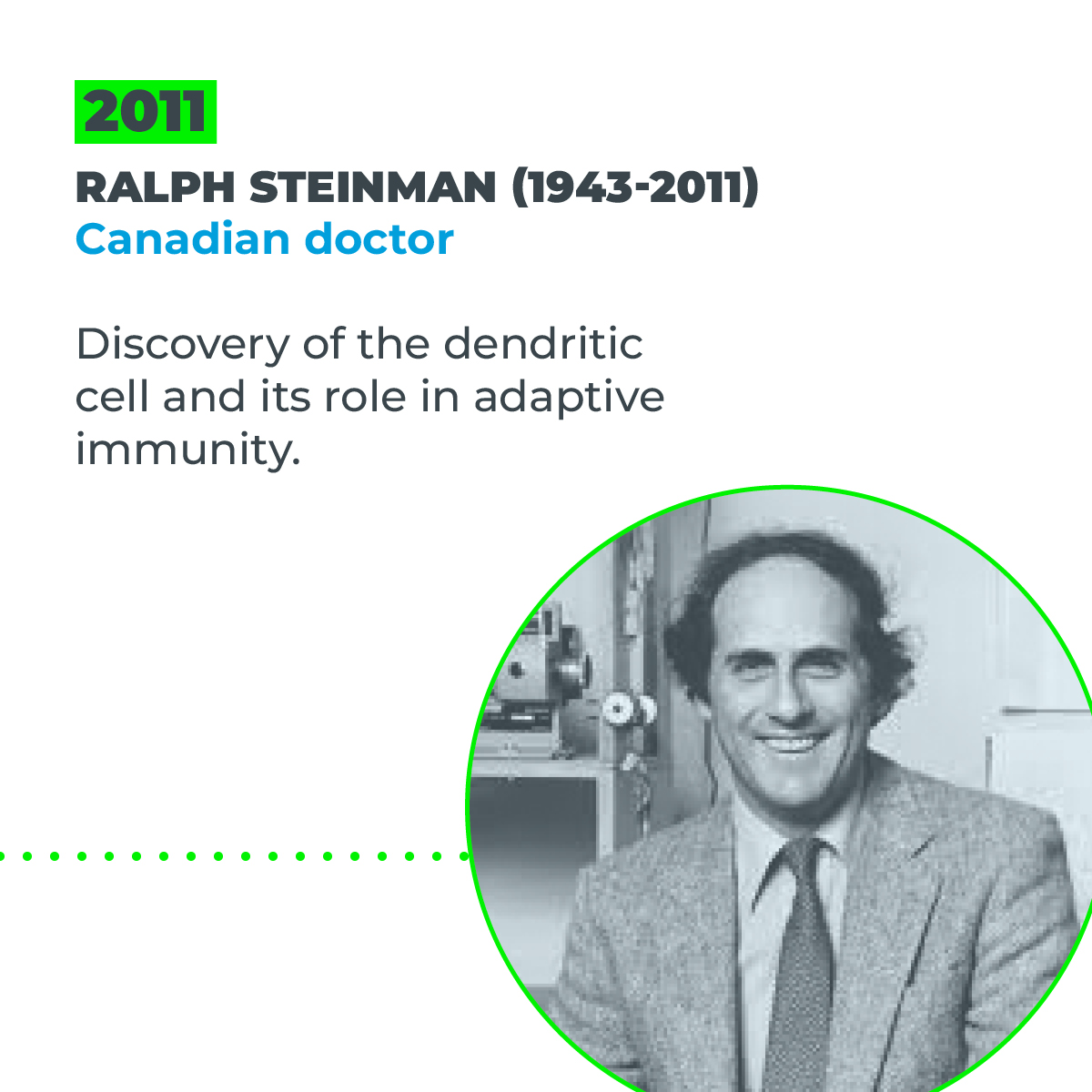

With the advancement of technologies used to develop immunosuppressive drugs over the following years and discoveries related to the immune system, what had been a nascent approach was transformed into a potential treatment option that was globally accepted by society.

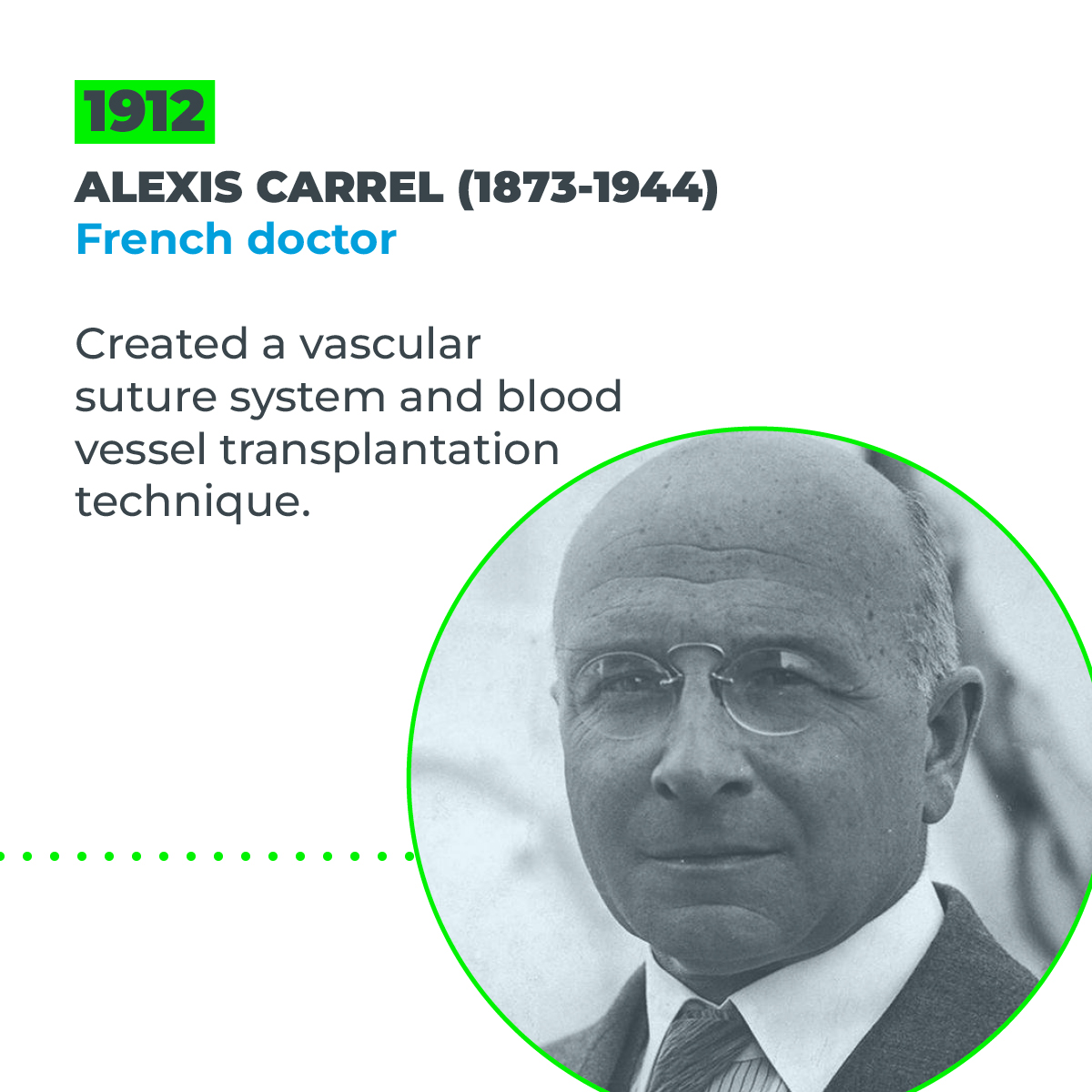

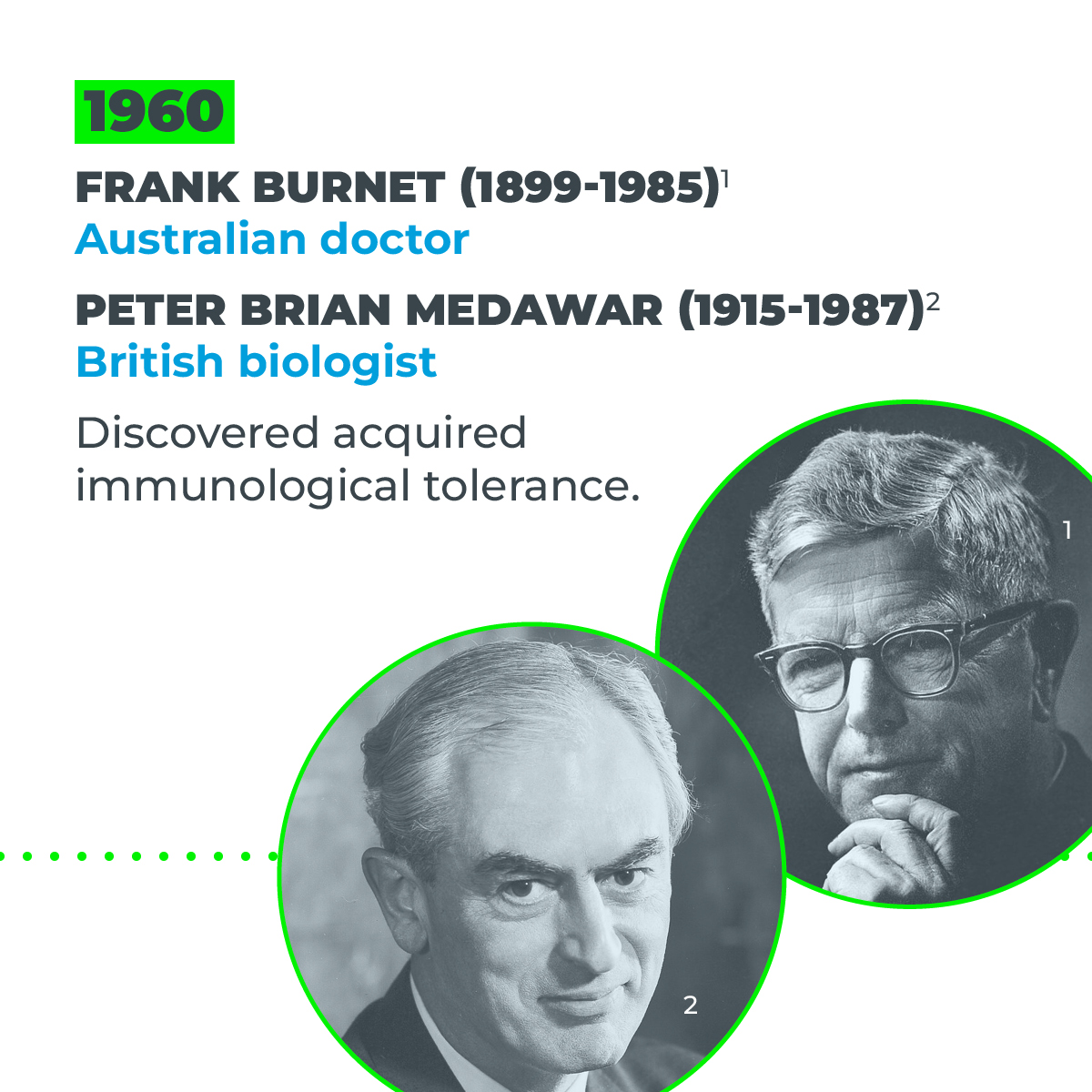

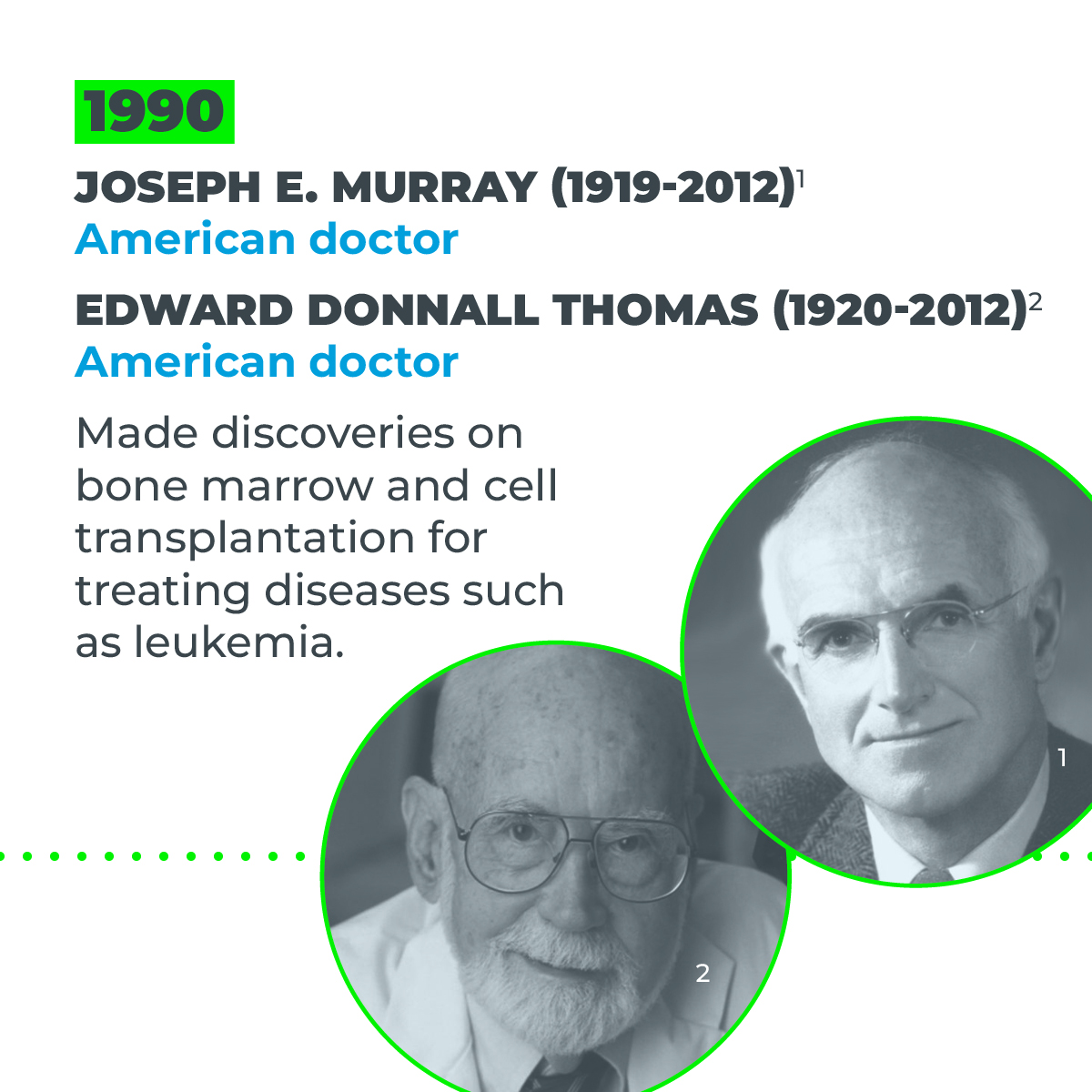

Scientific research on the topic has resulted in six Nobel prizes for 11 scientists and has helped to fully establish this social asset, represented by the moral advancement of society, especially in its acceptance of organ donations in cases of brain death, enabling many other people to survive.

The donation/transplant process has faced numerous challenges and several phases along its journey, including:

- Individualization of immunosuppressive therapy

- Advances in the clinical assessment of donors and recipients

- Less invasive surgical techniques, improving patient survival

- Systematization of the organ procurement process, with new methods for delivering bad news and supporting the families of donors

Scientists continue to seek answers to the many ethical questions. They study and deepen our understanding of patient safety, validate quality instruments, propose management tools to improve results, analyze economic information to demonstrate the direct and indirect costs of the process, and measure quality of life and adherence to therapies proposed by the multidisciplinary team.

They also influence clinical laboratory and image analysis methods as new findings direct new medical approaches, develop mathematical models for predicting survival, and thus enable organs to be allocated based on the best match between donor and recipient. Further still, they innovate through the development of organ perfusion machines and transport boxes.

However, with successful transplants resulting in decreased mortality and increased survival, the number of people on transplant lists has increased significantly, while many still do not have access to this form of treatment.

To ensure equitable access to transplants, we need to come up with new ways of identifying the barriers that stop some people accessing transplant lists, to reduce the inequities that still exist in this area as much as possible.

This is a challenge for which science is continuously seeking solutions—the donation/transplant process is part of a highly complex healthcare system and therefore has a high social and financial cost.

To foster equity, every level of the healthcare sector needs to be involved in finding ways to make transplantation a sustainable option for whoever needs it.

The principles of Brazil’s national public health system (SUS) serve as a basis for the development of combined strategies and tools, such as interdisciplinary clinics, reference teams, and unique therapeutic projects.

The challenges faced by the healthcare sector are clear, especially in primary care. The diabetes epidemic, for example, is increasing the number of patients with kidney failure, leading them to transplant lists.

Science, therefore, is tasked with identifying new ways to improve the donation/transplant process and proposing methods that effectively increase the number of donors and equitable access to organ, tissue, and cell transplants.

In response to these challenges, scientists are exploring the possibility of artificial organ production, xenotransplantation (using organs from other species), and production through regenerative medicine.

The latter represents a potential way of reducing the inequality between the number of organ and tissue transplants and the rising number of people on transplant waiting lists. But the field is still under development.

While some scientists are racing against time to find new ways to increase the supply of organs, tissues, and cells, others are striving to improve existing care processes, to make them more efficient and effective.

One such process is the development of quality and safety systems, with indicators that identify areas needing improvement and mathematical formulas for allocating organs and assessing needs and opportunities, designed to offer sustainable mechanisms for this form of treatment to the agencies involved.

As part of this quest for improvement, the World Health Organization (WHO) approved Resolution WHA63.22 at the 63rd World Health Assembly in 2010. The resolution, which covers “biosurveillance and its principles,” states that it is sensitive to “the need for data on adverse events and reactions associated with the donation, processing, and transplantation of human cells, tissues, and organs to be shared with the relevant bodies for analysis.”

The management of information gathered through monitoring, surveillance, evaluation, and risk management activities relating to the donation and transplant process therefore needs to be improved.

On top of this, indicators are needed that make it possible to analyze the number of countries with protocols for the notification, surveillance, and management of adverse events (reported to a biosurveillance system established and run by national authorities). This is the commitment made by WHO member countries.

Regional action plan

Another recent initiative was the 161st Session of the Executive Committee of the Pan American Health Organization (PAHO) in 2017, where strategies were drafted and a regional action plan was formulated for the Americas on the topic of organ, tissue, and cell donation and transplantation, titled “Strategy and Plan of Action on Donation and Equitable Access to Organ, Tissue, and Cell Transplants 2019–2030.”

Brazil was the first country in Latin America and the Caribbean to fulfill one of the plan’s targets of establishing a national biosurveillance system and contributing to international organizations by implementing transparent biosurveillance actions, coordinated by the Brazilian Health Regulatory Agency (ANVISA).

Finally, health workers, managers, and authorities from different sectors of society need to actively make a commitment to tackle the sale of organs worldwide, as described in the most recent version of the Istanbul Declaration in 2018.

They must also strive to encourage the ethical, safe, and responsible donation of organs, tissues, and cells, to promote greater equity and fair access with voluntary and free donation, as recommended by the WHO. This would ensure adequate treatment for everyone who needs a transplant, giving society back the high public investment made in SUS, a successful state policy.

Bartira de Aguiar Roza is an associate professor at the Nursing School of the Federal University of São Paulo (UNIFESP), head of the Study Group on Organ, Tissue, and Cell Donation and Transplantation (GEDOTT/CNPQ), and collaborating professor at the PAHO/WHO’s Department of Innovation, Access to Medicines, and Technology.

Opinion articles do not necessarily reflect the views of Science Arena or Hospital Israelita Albert Einstein.

*

This article may be republished online under the CC-BY-NC-ND Creative Commons license.

The text must not be edited and the author(s) and source (Science Arena) must be credited.