#Interviews

#Interviews

José Gomes Temporão: “Prevention must guide the fight against cancer”

Tackling cancer goes beyond treatment and must be viewed as a sociopolitical challenge, says FIOCRUZ researcher and former Minister of Health

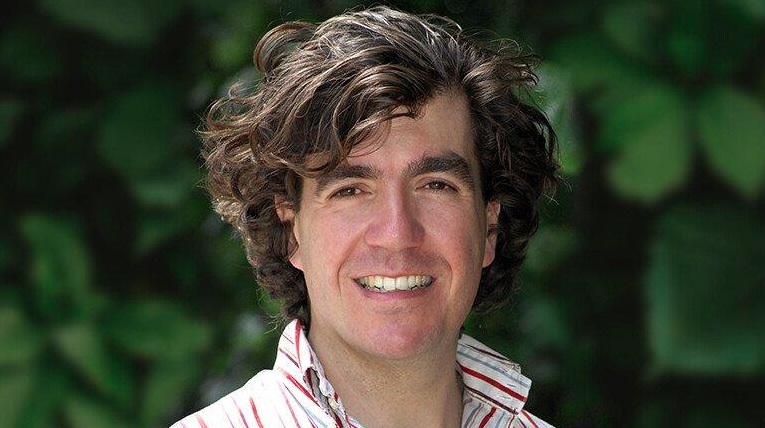

José Gomes Temporão, from FIOCRUZ: “Cancer is a multifaceted issue, and preventive measures can effectively contain its spread.” | Image: Sérgio Velho Junior/FIOCRUZ Brasília

José Gomes Temporão, from FIOCRUZ: “Cancer is a multifaceted issue, and preventive measures can effectively contain its spread.” | Image: Sérgio Velho Junior/FIOCRUZ Brasília

Cancer is the leading cause of death in hundreds of Brazilian municipalities and remains one of the greatest threats to global health, with projections of more than 35 million new cases by 2050, according to the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) of the World Health Organization (WHO).

Despite advances in early detection and treatment, public health physician José Gomes Temporão, Brazil’s Minister of Health from 2007 to 2011, cautions that centering cancer policy on high-cost technologies—often inaccessible to most people—cannot continue.

“It is essential that health systems, researchers, public managers, and civil society intensify their efforts to combat cancer, placing prevention and early diagnosis at the center of their strategies,” he told Science Arena.

According to Temporão, placing greater emphasis on prevention—without neglecting the need for equitable access to effective treatments—is what can truly curb the advance of cancer and reduce its growing impact on the population.

A researcher at the Oswaldo Cruz Foundation’s Center for Strategic Studies (CEE/FIOCRUZ), Temporão has long advocated for a change of direction: replacing late, reactive responses with proactive policies grounded in prevention, health promotion, and the strengthening of primary care.

It is from this perspective that the former minister is one of the organizers of the International Seminar on Cancer Control in the 21st Century: Global Challenges and Local Solutions, to be held on November 27 and 28 in Rio de Janeiro, with live broadcast and the participation of authorities and specialists from several countries.

In the interview below, Temporão discusses the structural obstacles to tackling cancer in Brazil, including technological dependence. “Cancer is a multifaceted problem that goes far beyond medicine—it is also a social and political challenge,” he summarizes.

Science Arena – What makes cancer such a complex issue?

José Gomes Temporão – It is an incredibly complex problem, with more than a hundred very different pathologies.

Beyond genetic factors, cancer risk is shaped by obesity, sedentary behavior, smoking, alcohol consumption, ultra-processed foods, sun exposure, environmental pollutants, and workplace carcinogens.

The issue is multifaceted and extremely complex because it involves everything from health promotion policies—educating, guiding, and raising awareness about these risk factors—to treatment, which is highly complicated: the earlier the diagnosis, the better the prognosis.

Treatment may require chemotherapy, surgery, and radiation therapy. In situations where medicine can no longer offer the prospect of cure, dignified and humane palliative care becomes essential.

What is the main problem with how cancer is approached today?

The issue is usually framed primarily through the lens of treatment, emphasizing new technologies and therapeutic methods, while health promotion and prevention receive far less attention.

The seminar we will hold this month aims to broaden this debate, addressing topics ranging from genetics and environmental exposure to promotion, prevention, diagnosis, and care, underscoring the complexity of the issue and the need to consider multiple dimensions beyond conventional treatment.

What is the situation regarding public policy in Brazil?

From a regulatory standpoint—laws, standards, and protocols—we are very well served. Last year we passed a law on comprehensive cancer care that is quite advanced, perhaps one of the most advanced in the world.

However, when you look at how these policies translate into care, there are numerous weaknesses: difficulty accessing services, poor organization of the care pathway, and long waiting times before treatment begins.

The seminar will highlight primary care. Why?

This may surprise some people—after all, cancer usually brings to mind hospitals, MRIs, chemotherapy, and surgeons.

But in reality, if we want to talk about early diagnosis, health promotion, and prevention, primary care is essential.

We have diseases that can be prevented by vaccination: the HPV vaccine prevents cervical cancer, and the hepatitis B vaccine prevents liver cancer.

Yet when you look at current vaccine coverage levels, in several states they are low. We are experiencing the consequences of what occurred during the pandemic and the wave of denialism.

Do community workers play a role in the fight against cancer?

Without question. In Brazil, people’s first point of contact with the health system is family health care. We have 150 million Brazilians covered by the Family Health Program (now the Family Health Strategy).

Community health workers visit households monthly and speak with residents in their homes. They can identify excessive alcohol consumption, check whether vaccinations are up to date, note if anyone smokes, advise them to quit, and refer them to the Unified Health System (SUS).

How can new technologies support primary care?

Primary care is central. With the scientific advances and the development of new artificial intelligence (AI) technologies, it is not unreasonable to imagine that, in the near future, family doctors across the country will have access to highly accurate diagnostic tools.

One example is liquid biopsy: with a simple blood sample, it may be possible to diagnose several pathologies, including abnormal growths. Imagine the impact this would have on care and early diagnosis.

When you talk about prevention, what limitations does the health sector face in relation to major economic players?

This is an extremely important point. Brazil already offers an example to the world: we succeeded in banning cigarette advertising across all media. We reduced the prevalence of smoking in the adult population from 30% in the 1970s and 1980s to 10% today. Unfortunately, the industry has now shifted its strategy and is enticing teenagers and children to use electronic cigarettes.

What is the role of public health in all this?

Public health also has a duty to speak up. If I remain silent when soft drink consumption, ultra-processed foods, or a lack of fiber-rich foods may lead many people to develop cancer in a few years, I would be dishonest. Of course, we constantly face lobbying from these industries.

How do social issues impact health?

Let’s talk physical activity. The WHO recommends 150 minutes per week of walking or some other type of exercise to prevent various diseases, including cancer. But when you analyze this in light of structural conditions that often hinder regular exercise, you reach what we call the social determinants of health—in other words, health is politically and socially determined.

Some striking figures have just been released in São Paulo: the city’s overall infant mortality rate is about 10 deaths per 1,000 live births before one year of age.

However, when you break it down by neighborhood, some areas record 30 deaths per 1,000 (the poorer neighborhoods), while others have 5 per 1,000 (the wealthier neighborhoods). The average is never a good indicator—the average may be 10 per 1,000, but it does not reflect the actual disparities.

Once cancer has developed, what are the challenges?

The chances of curing cancer are much higher when diagnosis and treatment begin quickly, but delays in the process—with long waiting lists for tests, surgeries, and access to medication—remain common in Brazil and vary by region. Prolonged waits can turn a treatable case into an advanced disease, compromising the patient’s prognosis and worsening inequalities in access to cancer treatment.

Can the SUS provide all the necessary technologies?

Does the SUS budget have the financial resources to offer all internationally validated technologies, approved by the Brazilian Health Surveillance Agency (ANVISA), to every Brazilian with cancer? Not today. There is an entire economic and financial dimension involved in this debate.

What is the role of telemedicine in cancer control?

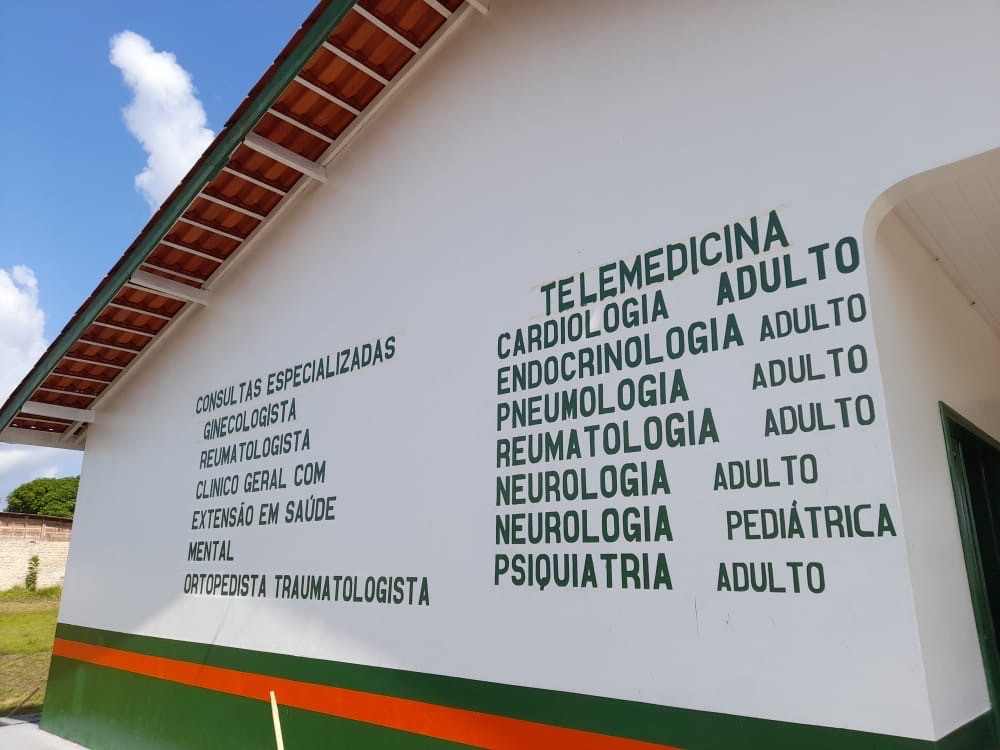

Telemedicine—or, more broadly, telehealth, which also involves other professionals—can be a very useful tool. In primary care, for example, when a family doctor suspects something but lacks the tools needed for a diagnosis, they can consult in real time, including with the patient beside them, with a specialist at any major center.

Can you give an example?

There are initiatives such as TeleAMES, a project by the Einstein Hospital Israelita—part of the Ministry of Health’s Institutional Development Support Program for the Unified Health System (PROADI-SUS)—which uses telemedicine to expand access to medical specialists for populations in more remote areas of the North and Midwest.

A consultation between the local doctor and the specialist can greatly assist in diagnosis and treatment.

Even without local resources to confirm diagnoses, family doctors working in health centers and clinics can consult specialists in real time and receive technical support, streamlining the process and reducing travel costs.

The event will take place a few days after COP30. How can we relate climate change and cancer?

This is perhaps one of the challenges of our event; the program attempts to address this issue. The WHO estimates that by 2030 cancer will likely be the leading cause of death globally, disproportionately affecting developing countries.

The highest number of deaths does not occur in developed countries, but in developing nations—in Africa, Latin America, and parts of Asia.

It is essential to bring the discussion on climate and health to society.

This is not simple, because dominant thinking remains focused on medical treatment—which mobilizes more resources, more attention, and more controversy—rather than on prevention.

What are the ethical issues involved?

These are extremely important questions that cannot be ignored. Take the debate around rare diseases, for example: a very serious disease affects 500 Brazilians who will die. The treatment exists, but it is extraordinarily expensive, prohibitively so. Should they receive it or not?

These are ethical dilemmas. Ultimately, it is not doctors who should make these decisions, but society—transparently and with clear criteria.

*

This article may be republished online under the CC-BY-NC-ND Creative Commons license.

The text must not be edited and the author(s) and source (Science Arena) must be credited.