#News

#News

Event debates the role of science in tackling urgent global challenges

AI, the climate crisis, and regional inequalities on the agenda at the 17th TWAS General Conference in Rio de Janeiro

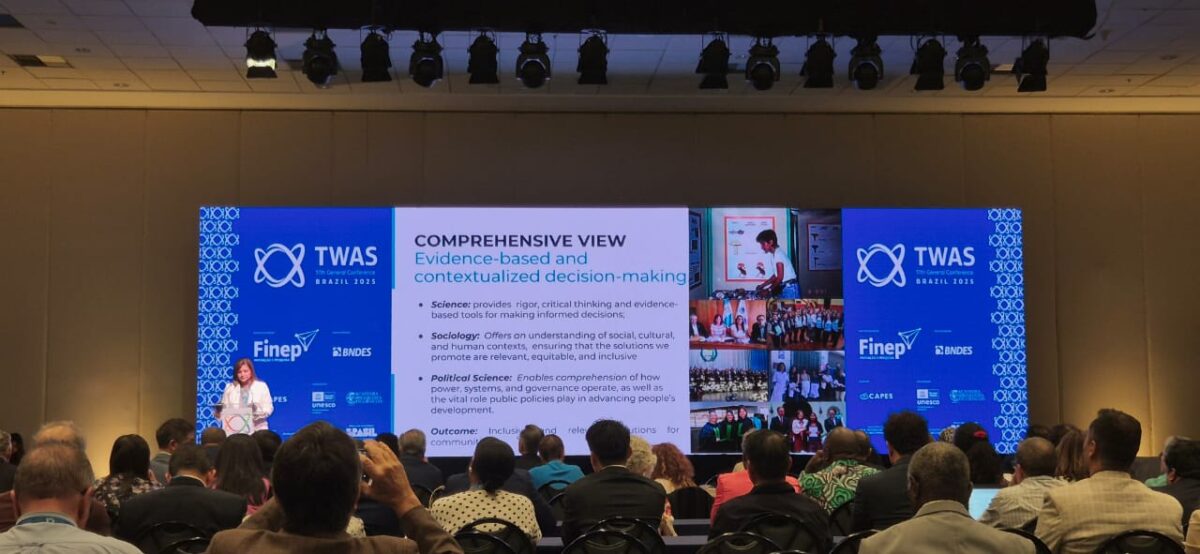

The first day of the 17th TWAS General Conference in Rio de Janeiro featured debates on scientific cooperation and solutions to challenges such as climate change and the impact of AI on research | Image: Bruno de Pierro

The first day of the 17th TWAS General Conference in Rio de Janeiro featured debates on scientific cooperation and solutions to challenges such as climate change and the impact of AI on research | Image: Bruno de Pierro

Science and the way knowledge is produced are changing—and low- and middle-income countries may be in a position to lead this transformation. To do so, domestic inequalities need to be tackled, and space disputed with large corporations in areas such as artificial intelligence (AI), with long-term public funding guaranteed.

These points were discussed during the first panel at the 17th General Conference of the World Academy of Sciences for the advancement of science in developing countries (TWAS); the organization is headquartered in Italy and linked to the United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization (UNESCO).

The gathering, which commenced on September 29 and continues until October 2 in Rio de Janeiro*, is organized in partnership with the Brazilian Academy of Science (ABC) and brings together authorities and more than 300 scientists from around the globe to discuss scientific cooperation and solutions to current challenges, such as AI and climate change.

“We need the critical mass mobilizing everywhere to deal with modern challenges,” said Lidia Brito, UNESCO assistant director-general for natural sciences, with a reminder that in order to form a critical mass in strategic areas, “you need to train 10,000 people so that 1,000 make the difference.”

Brazilian physicist and TWAS executive director Marcelo Knobel presented a survey conducted by Carlos Henrique de Brito Cruz, senior vice president at Elsevier Research Networks in the UK, using the Scopus citation database (1970–2024).

The data show that currently 60% of papers published across different knowledge areas originate from low- and middle-income countries.

The number of authors in these countries grows by 10% per year—double the rate recorded for more wealthy nations. Even without China, the rate for the 28 biggest low- and middle-income countries taken together is growing faster than the European Union and the UK combined.

Social demands and local experiences

This growth is not just in terms of volume. There are more citations and higher levels of leadership in research linked to the UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDG).

In the case of SDG 2 (zero hunger), the participation of low- and middle-income countries is even more expressive.

Knobel sees this advancement as the fruit of decades of investment in training, particularly in graduate programs. These efforts, he says, sustain research projects more in tune with social demands and local experiences.

“Working with low- and middle-income nations is no longer an option—it has become a necessity for the faster and better advancement of knowledge,” said Knobel.

“More ideas coming out of these countries means more knowledge based on local experiences, and firmer leadership in the definition of agendas.”

Unequal realities

Despite promising numbers, the panelists warned that there are still many challenges, such as gender inequality in science.

They also highlighted that what has been dubbed as the “Global South” may be hiding an unequal reality: advances in science are concentrated in upper-middle-income countries (such as China), which are invested in long-term strategies, while many low-income nations (such as Angola) have weak universities and little scientific qualification.

This situation is exacerbated by the emergence of technologies such as AI, quantum computing, and semiconductors in the midst of a geopolitical scenario of fierce competition, protectionism, and ever-increasing barriers to cooperation and knowledge transference.

According to Luis Manuel Rebelo Fernandes, executive secretary at the Brazilian Ministry of Science, Technology, and Innovation (MCTI), this imbalance primarily affects lower-income countries, which are among those least prepared to adopt innovations such as AI and green hydrogen, and run the risk of missing out on the opportunities inherent in a low-carbon economy.

This polarization, says Fernandes, would leave regions of Latin America, the Caribbean, and sub-Saharan Africa particularly vulnerable.

In the specific case of AI, the risk is that the lack of infrastructure for data and computing capacity widens the divisions between wealthy and poorer countries.

There are still environmental impacts: the technology demands enormous volumes of water and energy, in direct competition with the basic needs of vulnerable regions.

“The trends that must modulate science in the Global South include the transition to integrated solutions—connecting water, energy, food, and climate—the digital leap in terms of AI and green and energy transitions,” said Akissa Bahri, a former minister of agriculture, water resources, and fishing in Tunisia.

New science contract

International cooperation has emerged as an inevitable axis for sustaining these solutions, whether through horizontal models between countries of the Global South, or in arrangements that include the Global North.

Lidia Brito believes that this would also be a way of adapting to the new science “contract.”

“Governments used to fund scientists in seeking new knowledge for the benefit of society. The biggest investors these days are the companies, and this means that it is they who define where and for whom the research is conducted, who may access it, and who benefits from it,” said the UNESCO representative.

In this context, open access to scientific output gains weight in discussions.

As well as language barriers, the high rates of publication demanded by scientific publishing houses have been identified as an impediment that threatens to “kill science” in many Global South countries.

“We cannot generalize, as there are different situations in the countries across all of these continents and regions,” said the MCTI’s Fernandes.

“However, the understanding in Brazil is that cooperation in science, technology, and innovation is key for development in the Global South to strengthen sovereignty and technological independence and reduce global imbalances.”

*The Science Arena team attended the conference at the invitation of TWAS.

*

This article may be republished online under the CC-BY-NC-ND Creative Commons license.

The text must not be edited and the author(s) and source (Science Arena) must be credited.