#Careers

#Careers

Fighting Alzheimer’s with science and empathy

Brazilian biologist is leading research that seeks to develop a simple, less invasive method for diagnosing the disease that affects her mother

According to the Pan American Health Organization (PAHO), there are 10.3 million people with Alzheimer's disease in the Americas | Image: Shutterstock

According to the Pan American Health Organization (PAHO), there are 10.3 million people with Alzheimer's disease in the Americas | Image: Shutterstock

Three years ago, Maria Ivone Valentini Cominetti was diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease. “She started with the typical symptoms of memory loss,” says her daughter Márcia, 49. Márcia Cominetti is a biologist who specializes in Alzheimer’s and is head of the Biology of Aging Laboratory (LABEN) at the Federal University of São Carlos (UFSCar), in the state of São Paulo.

“I don’t know if it was fate or coincidence,” Cominetti says about the onset of her mother’s illness. “I don’t know if it’s good to know everything that might happen to her, or if ignorance would be better. But every person with dementia is different. The way the disease progresses depends on many factors,” she says.

According to Cominetti, her mother is doing very well and remains lively and happy. “She is aware of everything, she has her own opinions, and she has remained active since the diagnosis. The disease is progressing slowly in her case,” she says.

In one of Cominetti’s most recent investigations, she searched for a more accurate method for diagnosing Alzheimer’s—something as simple as a blood test.

Alzheimer’s is currently diagnosed by asking a set of questions about cognition and memory. If a patient does not achieve the score expected for their age and education level, the doctor can order biochemical tests to check for nutritional deficiencies that may be causing some form of dementia, or imaging tests, such as an MRI or CT scan, to help confirm the diagnosis.

Another test that can aid the diagnostic process is a lumbar puncture, which involves collecting a sample of cerebrospinal fluid (which circulates through the central nervous system).

“Imaging exams are expensive and not everywhere has the equipment,” explains the researcher. “A lumbar puncture is an invasive procedure that is painful and can cause side effects, especially in elderly people who may have other comorbidities. Questionnaires, meanwhile, are not enough to confirm a diagnosis.”

“A blood test is an important possibility to investigate as a cheaper, less invasive, and more accurate way to diagnose Alzheimer’s,” says Cominetti.

The idea is to screen the blood of people with suspected Alzheimer’s for specific proteins related to the disease. Neurologists already look for tau proteins and amyloid beta in MRI scans when seeking to diagnose Alzheimer’s.

They are too diluted to be identified in the blood, but a third protein, called ADAM10,which prevents the formation of amyloid beta,may offer an important clue.

High levels of ADAM10 in the plasma of a person with Alzheimer’s may indicate that the protein is not acting in the brain, therefore facilitating progression of the disease.

“Until a few years ago, there was no equipment sensitive enough to detect these biomarkers in the blood. It could only be identified in the cerebrospinal fluid that circulates through the brain,” says Cominetti. “Now, however, there are ultra-sensitive devices that allow for much less invasive examinations,” adds the researcher.

Biomarker validation

Scientists at LABEN, led by Cominetti, have been investigating ADAM10 since 2017, attempting to validate it as a blood biomarker to diagnose Alzheimer’s. The research is currently undergoing trials with volunteers aged over 60 years old.

“We took a very careful approach with these people because surprising as it may seem, after the last few years of government, they are wary of participating in research—they feel like guinea pigs,” says the biologist.

“We explained that we are going to do a health assessment and that we are working on finding an early diagnosis for Alzheimer’s,” she says.

The secret, according to Cominetti, is to be sensitive and empathetic with the volunteers. “There are ways to talk to an elderly person. You need to be attentive, patient, and to study the best strategies,” she advises.

More information about Alzheimer’s

Click on the topics below to learn more:

-

How many people have Alzheimer's worldwide?

-

There are 50 million people with the disease worldwide. According to estimates by Alzheimer’s Disease International, this figure could reach 74.7 million by 2030 and 131.5 million by 2050, due to the aging global population. The Pan American Health Organization (PAHO) estimates that 10.3 million people have the disease in the Americas.

-

Can the disease be slowed down or even prevented?

-

A paper published in The Lancet in August estimated that up to 45% of all dementia cases could be delayed, slowed down, or even prevented. Alzheimer’s is the most common form of dementia in humans.

-

What can be done throughout a person’s life to reduce their risk of developing the disease?

-

A paper published in The Lancet gave specific recommendations on how to reduce the risk of Alzheimer’s and dementia in general. Many of them require collective efforts and the development of public policies. Some of the measures include:

- Ensuring high-quality education for all and encouraging cognitively stimulating activities in midlife

- Treating depression effectively

- Encouraging physical exercise

- Reducing tobacco use through education, price control, and smoking bans in public places

- Detecting and treating elevated low-density cholesterol (LDL), known as “bad cholesterol”

- Reducing excessive alcohol consumption through price control and greater public awareness of the risks of drinking too much

- Reducing exposure to air pollution

-

Is there stigma associated with the disease?

-

- According to the World Alzheimer’s Report 2024, 88% of people with dementia say they have experienced discrimination

- The report is supported by a global survey of more than 40,000 individuals in 166 countries

- The study highlights a lack of knowledge among health professionals, 65% of whom incorrectly believe that Alzheimer’s and dementia in general are a “normal part of aging”

- More than a quarter of people worldwide incorrectly believe that there is nothing we can do to prevent dementia, a figure that has risen in low- and middle-income countries from 20% in 2019 to 37% in 2024

- A report by Alzheimer’s Disease International warns that a lack of understanding about the disease can delay diagnosis and access to treatment

Cominetti expresses surprise that some people diagnosed with the disease in its early stages maintain an active life. “They know they have the disease and they work around it; if they forget a word, they choose a similar one to use instead,” says the researcher.

“It’s wonderful to see how people deal with dementia knowing they have it, how they find strategies to continue being as active as possible and living life to the fullest.”

In the early stages of the disease, patients are still able to hold opinions and make decisions. “Some people think that when a person has dementia, it’s the end—but it’s not. The person still has their own opinions and feelings. What happens is that in the most serious phase, it becomes difficult to interpret the signs they give us,” says the biologist.

A career shaped by science

Cominetti is fascinated by the study of aging, but that was not always the case. At the beginning of her career, shortly after she graduated from the Federal University of Santa Catarina (UFSC) in 1998, she worked in cellular biology, studying shrimp.

For her PhD, which she did at UFSCar, she studied venomous snakes. “There are several molecules in snake venom that cause hemorrhages and inhibit the proliferation of certain cells. This relates to cancer, which is nothing more than an uncontrolled proliferation of cells in different tissues,” she says.

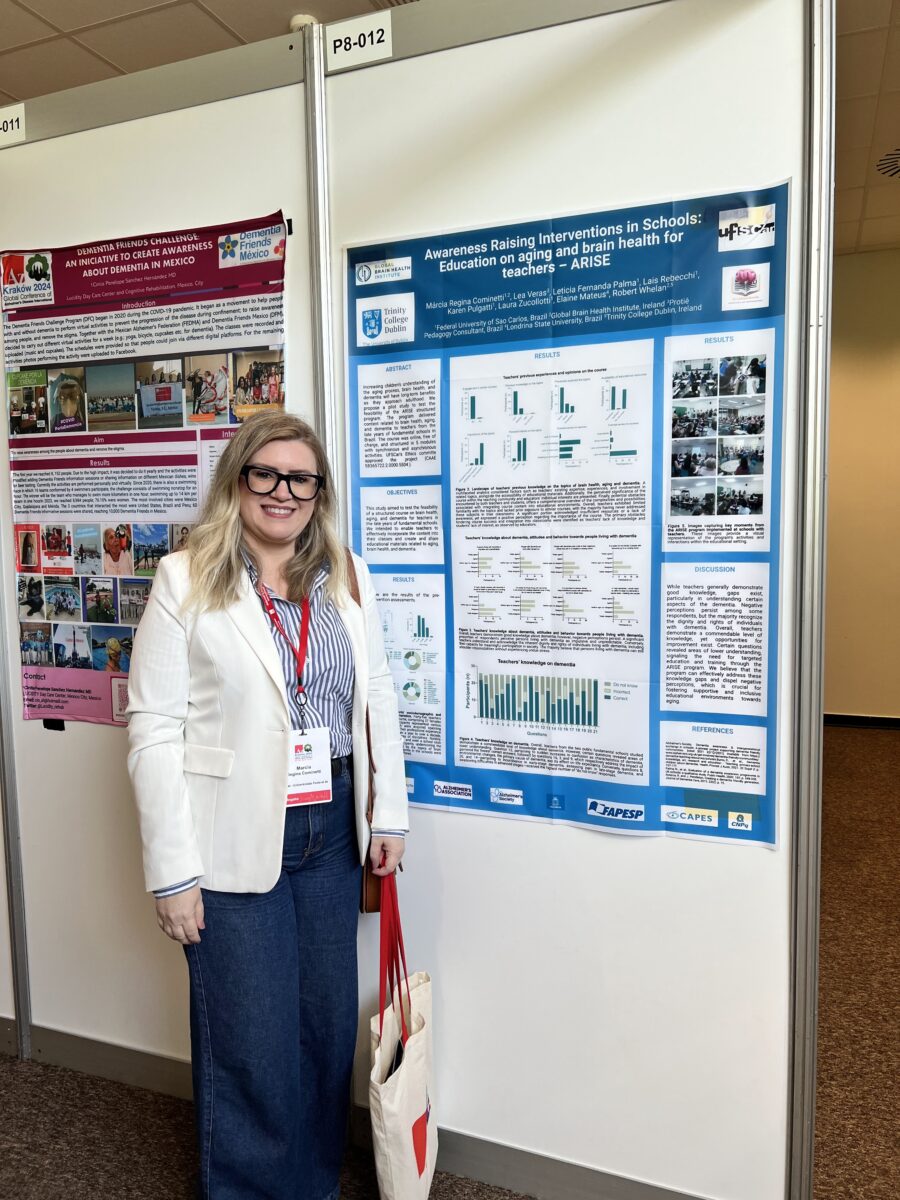

Research into how these molecules function in cancer cases led her to spend a year in Paris, France, where she had a remarkable experience despite difficulties with the language. She also lived in Ireland, where she mastered English more easily and was part of the Global Brain Health Institute (GBHI) at Trinity College.

Upon returning to Brazil in 2006, she continued her research for a further three years with a postdoctoral fellowship, until she got a job teaching on the recently created gerontology course at UFSCar.

“I don’t think anyone really knew what it was,” she jokes.

Given the mission of teaching basic subjects about aging, Cominetti herself needed to study. “As a biologist, I understood the basics of aging, but I had to learn a lot of things that were not then in my wheelhouse,” she recalls.

As she began to understand more about aging, she fell in love. “I don’t think we define our own path, but the path defines us—it shapes us.”

Cominetti is about to turn 50, and with almost 25 years of knowledge about biology, cells, proteins, and aging, she hopes she can prepare her family for what is to come as her mother Maria Ivone’s Alzheimer’s progresses.

“With her, I put into practice everything I teach in my courses: physical activity, cognitive stimulation—I gave her some of the cognitive stimulation materials that we use in the lab—and I tell her to keep going to the supermarket,” says the researcher, who does not live near her mother, but plays an active role in her life and takes care of her together with her sister.

“I think it makes things easier, because I know what’s to come, but knowing this also makes things harder,” she says.

*

This article may be republished online under the CC-BY-NC-ND Creative Commons license.

The text must not be edited and the author(s) and source (Science Arena) must be credited.