#Columns

#Columns

In times of digital slavery

Although advances in science have taken civilization to new levels, a lack of oversight in the use of digital technologies can affect our sensory experience of the real world

Digital dependence and less connection with nature can lead to higher levels of anxiety | Image: Robin Worrall / Unsplash

Digital dependence and less connection with nature can lead to higher levels of anxiety | Image: Robin Worrall / Unsplash

The biggest inventions of the last millennium were transformational, profoundly impacting society, the economy, and science. This includes, from the fifteenth century onwards, electricity, the steam engine, and the telephone.

Over the last two centuries, we have experienced a true revolution.

Airplanes were created, as were nuclear energy, computers, the internet, artificial intelligence, and the atomic bomb, which caused mass destruction and took the lives of thousands of people in Hiroshima and Nagasaki, Japan.

We watched Neil Armstrong (1930–2012) walk on the moon on another invention, the television, in a black and white broadcast seen by more than 600 million people worldwide.

In health, vaccines have allowed us to manage diseases such as smallpox, measles, and polio in the last 200 years, culminating in the coronavirus vaccine.

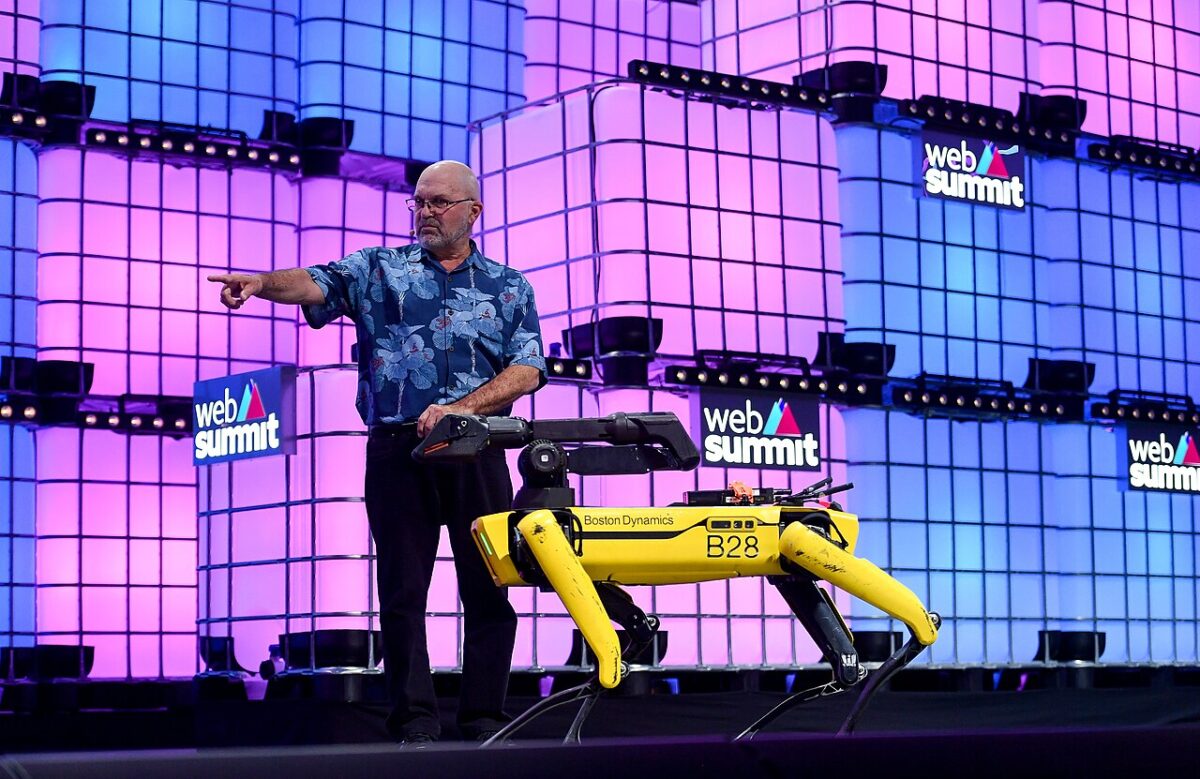

We have also witnessed the emergence of anesthesia, antibiotics, modern surgical techniques, robotics, and nuclear medicine, which has improved the diagnosis and treatment of various diseases, saving thousands of lives.

Inventions and technologies are not inherently good nor bad. It depends on how they are used.

They need to be used ethically, guided by the principles of freedom to grow and individual and collective health.

Digital dependence

We can use the smartphone, which you may be using right now to read this text, as an everyday example.

Despite the freedom afforded by the digital age, we paradoxically find ourselves more imprisoned than ever.

Smartphones were created to increase freedom of communication, but they have become a modern-day shackle that shapes our interactions, leisure time, and even our perception of reality.

Like Big Brother disguised as a personal assistant, they monitor us, collect data, induce certain behavior, and perpetuate cycles of dependency, depriving us of our sensory experience of the real world.

The digitization of life has resulted in new forms of servitude: we are always online, subjugated by hyperconnectivity.

Our agenda, itinerary, files, photos, passwords, they are all connected. Even access to other digital systems, because nowadays it is almost impossible to access any system without first receiving an access code via SMS or email.

A convenience that makes us healthier and more independent?

Researchers point out that prolonged exposure to screens affects mental health, increasing rates of anxiety and depression, and causing harm to children’s health.

Digital dependence shares similarities with other forms of addiction, having devastating effects on cognition and social interaction, but also on the way we relate to nature.

Another study showed that excessive use of smartphonesis related to higher levels of anxiety.

It also suggested that even at levels perceived as nonproblematic, smartphone use may negatively impact our feelings of connection with nature.

The greater the disconnect with nature, the less chance there is for people to enjoy the benefits it can have on their mental health.

The natural world, seen for centuries as a refuge for contemplation and inner peace, is giving way to a pixelated world only seen through screens.

Digital detox

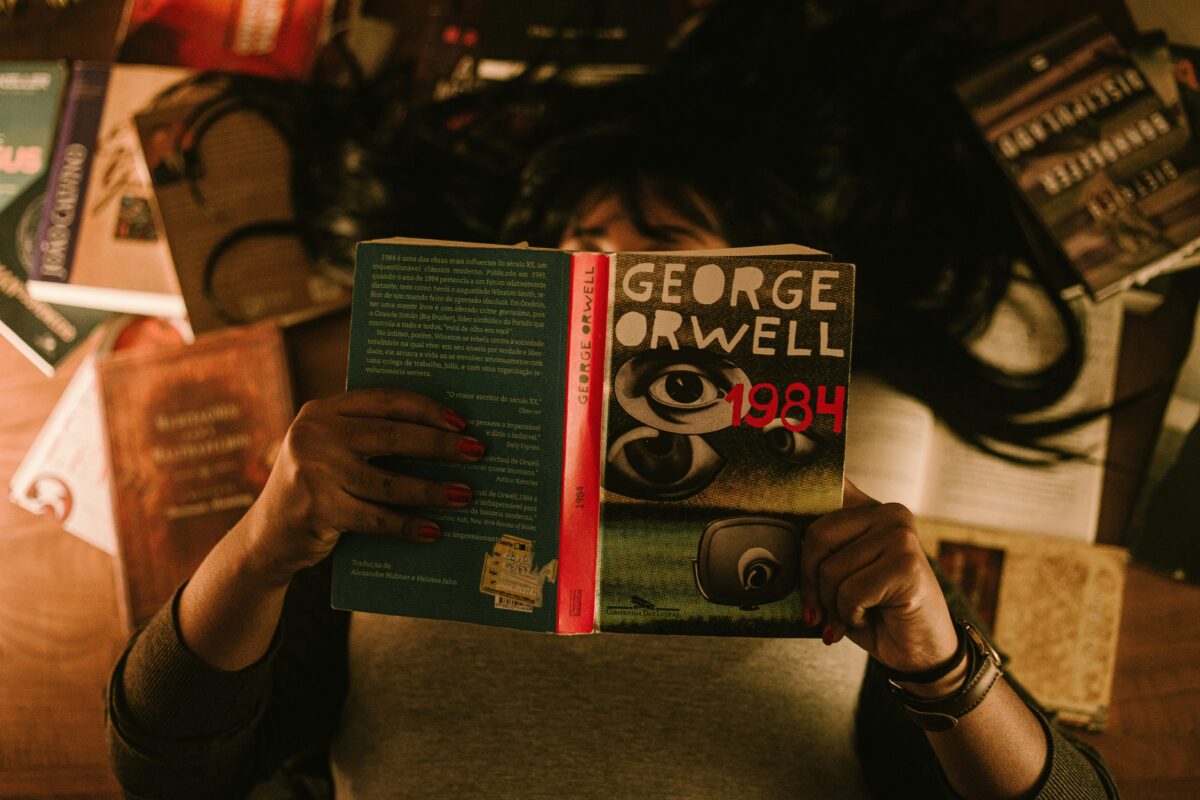

In the novel “1984,” George Orwell (1903–1950) imagined a world where people were controlled through absolute surveillance.

In “Brave New World,” Aldous Huxley (1894–1963) described a dystopia in which people passively accepted their own alienation, entertained by superficial distractions.

We are now living in a combination of these depictions: we are constantly monitored and at the same time kept in a perpetual state of entertainment and separation.

In his “Essay on Blindness,” Jose Saramago (1922–2010) warned: “I don’t think we did go blind, I think we are blind, blind but seeing, blind people who can see, but do not see.”

The greatest irony is that to be aware of this digital servitude, we rely on the very technology that imprisons us.

The “digital detox” and “technological minimalism” movements are attempting to restore our autonomy, but to do so they need to break down the structure of an increasingly digitalized society.

To break this cycle, we need to collectively reposition ourselves, by imposing limits on screen use, encouraging presence in the real world, and reconnecting with nature and ourselves.

Like Greek mythology’s Prometheus, who stole fire from the gods to set humanity free, we need to reclaim our time and attention from our own technological creations.

The question that remains is: are we brave enough to break our own chains?

Lis Leão is a senior researcher at Hospital Israelita Albert Einstein and head of the e-Nature Research Group for interdisciplinary studies on connections between nature, health, and well-being (CNPq).

Opinion articles do not necessarily reflect the views of Science Arena or Hospital Israelita Albert Einstein.

*

This article may be republished online under the CC-BY-NC-ND Creative Commons license.

The text must not be edited and the author(s) and source (Science Arena) must be credited.