#Essays

#Essays

Einstein the watchmaker

Reflecting on the consequences of our academic work can prevent unethical practices, although it does not guarantee that discoveries will not result in “atomic bombs”

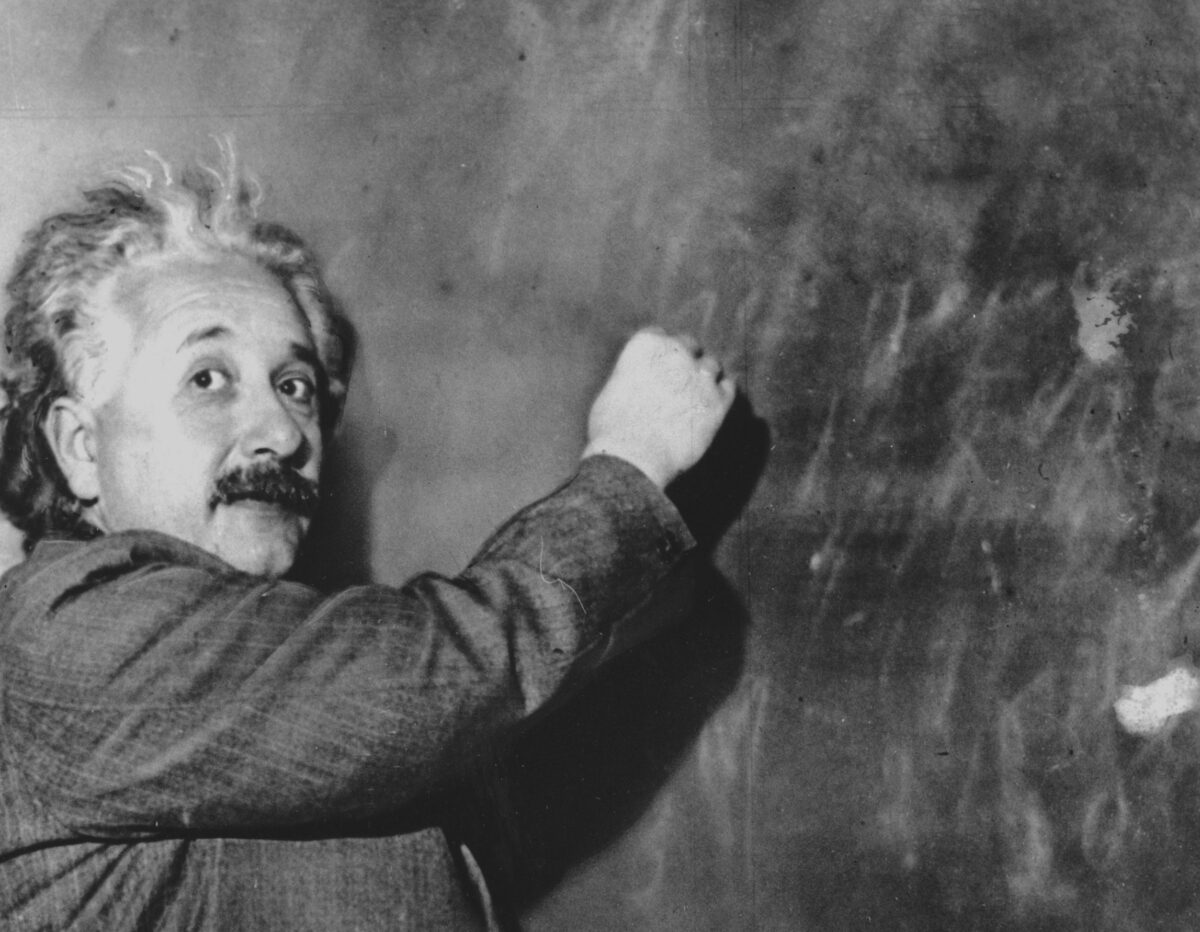

In The World As I See It, a book originally published in 1934, German physicist Albert Einstein (1879–1955), father of the Theory of Relativity, wrote that “today, scientists and technicians have a particularly heavy moral responsibility, because the progress of weapons of mass destruction is in their hands. That's why I think it's essential to create a ‘society for social responsibility in science.’” [free translation of the original in German] | Image: Associated Press/WikiMedia Commons

In The World As I See It, a book originally published in 1934, German physicist Albert Einstein (1879–1955), father of the Theory of Relativity, wrote that “today, scientists and technicians have a particularly heavy moral responsibility, because the progress of weapons of mass destruction is in their hands. That's why I think it's essential to create a ‘society for social responsibility in science.’” [free translation of the original in German] | Image: Associated Press/WikiMedia Commons

Baruch Spinoza (1632–1677), an emblematic European philosopher of modernity, linked ethics to the rational search for an understanding of the nature of things, including human nature. Thus, science, as the methodical investigation of phenomena in order to produce knowledge (with all necessary poetic license), suggests that reason is essential for ethical research.

I am pursuing this to add value to a field that is already so well explored from a regulatory point of view—such as the Research Ethics Committees (CEPs) and the Brazilian National Research Ethics Commission (CONEP)—and broad in the sense of human relations (morality, empathy, responsibility, justice, respect). Reason allows us to reach conclusions based on evidence and logical principles.

I propose that by thoroughly understanding what we are dealing with, where we want to go, and what the consequences will be, we will have a good clue as to how we can better relate to ethical and/or moral concepts in application research.

It is worth revisiting Spinoza and adding that, according to him, “all ethics present as a theory of potency, as opposed to morality, which presents itself as a theory of duty.”

I would like to emphasize here the legitimacy of curious research, which must be neutral and free of judgment, requiring (ethical) validation only in terms of its execution, but I am interested in reflecting on its implementation.

I had an exceptional PhD student, Marlon Ribeiro da Silva, a historian concerned with (social) ethics in technological developments. In his thesis, he used critical reading and reflection on classic works, such as Frankenstein by British author Mary Shelley (1797–1851), to jointly guide technology students in developing their products and processes.

The title of his thesis, “Arte, ciência e tecnologia: um coração partido e a literatura como remédio” (Art, science, and technology: A broken heart and literature as a cure), is thought-provoking and highly recommended.

The aim of first reflecting on the motivation and consequences of our academic work is avoiding unethical practices, although there is no guarantee that significant discoveries, such as nuclear fission, won’t result in atomic bombs; and of course, looking at history from the rear-view mirror is always simpler.

It is said that physicist Albert Einstein (1879–1955), one year before his death, lamented: “If only I had known, I should have become a watchmaker.”

I have been involved in research for decades, and I see that the curiosity for scientific knowledge prevents belief without explanation—which is why they call science the “church of reason.”

When we consider the motivation and the result of using our findings, we attach the word innovation to our research. In this context, we have some tools that can help our understanding and more ethical actions, such as medical design, mission-oriented research, and implementation research.

Medical design involves participative planning to define problems, strategies, and self-critique during the production process. Low-waste energy, focused and targeted light. I compare this role to that of an architect, who studies the behavior of a home’s future residents before proposing an appropriate design.

Here, we rely on reason, identifying and analyzing scenarios in advance, mapping strengths and weaknesses, using tools in an unbiased manner, and rigorously testing hypotheses, while always involving the user in the process.

Mission-oriented research, exemplified by the lunar mission ordered by John F. Kennedy (1917–1963) in 1961, to land a man on the moon and return him safely to the earth before the decade is out, at a cost of US$257 billion (current values), left a legacy of useful artifacts such as portable computers, carbon fiber, environmental education, astronautics, and the very appreciation of science.

It is about consciously pointing in a direction, creating conditions, and investing intensively in strategic areas for global well-being.

Implementation science involves the effective use, by many people, of previously tested and approved evidence-based solutions. Known barriers, whether structural (lack of access and resources such as time, funding, and equipment), cultural and social (resistance to change and the adoption of new practices or technologies), knowledge and skill-based (lack of adequate training or understanding), legislative and regulatory (outdated or restrictive laws and regulations), or those related to communication (ineffective dissemination regarding the benefits and procedures, post-truth) must be studied and considered in the design and implementation of our research to increase chances of adoption.

This more holistic view of ethics, which uses rationality as a basis for its decisions, must be aligned with the concepts of morality, responsibility, justice, and respect, not only so that we do no harm to society, but so that we do good, so that we do better.

Paulo Schor is an ophthalmologist, former director of technological and social innovation at the Federal University of São Paulo (UNIFESP), where he is an associate professor at the Paulista School of Medicine, and research manager for the São Paulo Research Foundation (FAPESP).

The opinion articles do not necessarily reflect the views of Science Arena and Hospital Israelita Albert Einstein.

*

This article may be republished online under the CC-BY-NC-ND Creative Commons license.

The text must not be edited and the author(s) and source (Science Arena) must be credited.