#Essays

#Essays

Health and urban planning: A historical look at open-air schools

Despite the lack of scientific evidence for natural medicine, open-air schools encourage us to rethink health and education beyond emergency situations

Children take part in an outdoor class under the trees at a primary school in Uttar Pradesh, northern India | Image: Shutterstock

Children take part in an outdoor class under the trees at a primary school in Uttar Pradesh, northern India | Image: Shutterstock

The understanding that microorganisms cause infectious diseases was established at the end of the nineteenth century. Microscopes, dyes, and increasingly sophisticated equipment made it possible not only to identify them, but also to describe their shapes and dimensions.

To convince the public, however, simply knowing that diseases were caused by invisible beings was often not enough. The fact that they can be found anywhere, even in the clearest water and the purest air, made the issue seem a little vague.

At the beginning of the Bacteriological Era, evidence-based and allopathic medicine coexisted, with therapies using the simplest natural resources in an attempt to treat diseases.

This included bathing in various types of water, exposing the body to the sun and high-altitude climates, a rustic (usually vegetarian) diet, and sometimes physical exercise.

These methods comprised the main approaches of natural medicine.

Originating from neo-Hippocratism and vitalism, natural medicine first emerged in the Germanic territories toward the end of the eighteenth century. Over the following centuries, it faced criticism and obstacles, primarily due to its empirical nature and lack of laboratory validation.

Its foundations were rooted more in a desire for greater contact with nature than in modern scientific principles, inspired by poetry (romantism) and philosophy, such as the ideas of Jean-Jacques Rousseau (1712–1778).

Natural medicine reached its peak at the end of the nineteenth century, at the same time as the Bacteriological Era began.

It was clear that scientific evidence had the potential to have a major impact in medical circles. Even so, changing people’s mentality takes longer, and it is not always possible to do so at the same pace as scientific discoveries and innovations.

Another factor to consider is that more than their scientific validity, health practices adopted in different historical circumstances are related to disputes between different fields of knowledge and social projects.

They are often the result of political and economic discord, and their social affirmation—the impact and success they achieve—depends largely on cultural context than simply on laboratory evidence.

In contrast to urban and industrial advances, natural medicine emphasized the appeal of natural elements such as water, fresh air, sunlight, natural food, and more broadly, a life spent outdoors.

It was believed that a supposed “return to nature” could ward off the harms attributed to urban and industrialized life, strengthening the human body and its organic defenses.

It was also in this context that the lebensreform (life reform) movement flourished, particularly in Germany. Life reform, a diffuse and fragmented social movement that aimed to transform the way people live to ensure they spent time outdoors in close contact with nature, gave a massive boost to the circulation of knowledge about natural medicine.

Therapeutic practices

At the end of the nineteenth century, a wide range of therapeutic practices, such as hydrotherapy, heliotherapy, and climatotherapy, were established within natural medicine.

Treatments using the sun and weather were often used to combat and prevent tuberculosis, a disease that had high mortality rates for decades until the widespread adoption of the BCG vaccine.

At a time when effective medicines were scarce, the knowledge and practices of natural medicine were adopted by many sanatoriums and bathhouses located far from major cities.

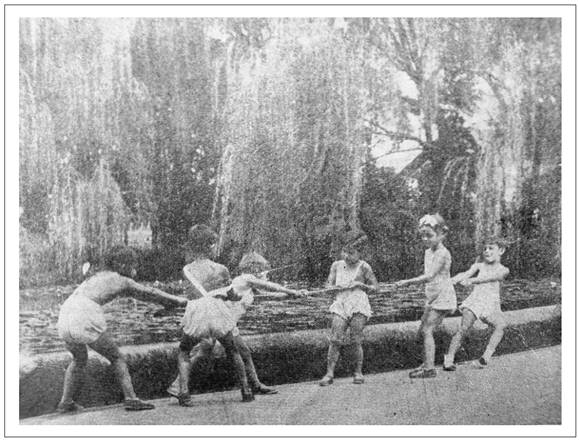

This knowledge also entered preventive and hygienic medicine, impacting urban planning and architecture. Its growth was also felt in the fields of education and childcare, leading to the creation of holiday camps and open-air schools in several countries.

Outdoor classes

One example in Brazil was a network of open-air institutions created in 1939 by the São Paulo State Department of Physical Education. It included the São Paulo Open-Air School, located inside Parque da Água Branca, where lightweight, portable tables, chairs, and blackboards were used to hold classes outdoors, generally under the trees.

The state department also helped town halls in the interior of the state to open children’s parks with the aim of stimulating enjoyment of the outdoors. Holiday camps were set up in Santos and Campos do Jordão, welcoming students from different regions of the state to spend time in the open air, enjoying the sun and the Atlantic Ocean or the high-altitude weather of the Mantiqueira Mountains.

Natural medicine began to decline in the 1950s, when people started to more strongly contest its principles. The rising levels of disbelief occurred in parallel with condemnation of the excesses of post-war eugenic medicine, with which natural medicine was often associated.

Natural medicine’s loss of credibility was also greatly exacerbated by its radical opposition to vaccination, the advantages of which were becoming clearly apparent.

Vaccines played a crucial role in the epidemiological transition of the twentieth century, during which infectious diseases were replaced by chronic and degenerative diseases as the leading causes of death.

This phenomenon was driven by advances in modern medicine and pharmaceutical science.

In contrast, natural medicine was gradually sidelined to the margins of official medicine, coming to be seen as alternative or complementary therapies and assuming new names, such as naturopathy and naturotherapy.

The decline of open-air schools was also caused by investments in the factory school model, which aims to accommodate the largest possible number of students within a given physical space in order to optimize resources and reduce costs. The São Paulo Open-Air School was transferred to a specially constructed building in the Lapa neighborhood in 1952. It consisted of six ground-floor classrooms with large windows and doors that opened out into six private open-air courtyards, allowing outdoor teaching to continue.

Over the following decades, however, its innovative architecture was gradually stripped away, with its internal courtyards being closed to accommodate a greater number of students in classrooms.

The pandemic, health, and urban planning

Much of this long story was forgotten in 2020, when the SARS-CoV-2 virus emerged and rapidly spread around the world. As quarantines and social distancing measures were imposed to contain the spread of the disease, a spotlight was shone on the historical relationships between epidemics, urban planning, and architecture, both in academic debate and in the press.

In many cases, the importance of the open air was emphasized once more as a prophylactic measure after enclosed spaces were identified as hotbeds of contagion.

Newspapers around the world published articles reviving the teachings of open-air schools from a bygone era, offering examples of how to safely resume classes and proposing new school architectures that would reduce the impacts of future epidemics.

As in other historical moments, a widespread and effective fight against an infectious disease like COVID-19 was only possible thanks to the development of vaccines—in this case created very quickly due to accumulated scientific knowledge, global collaboration, the use of innovative technologies, and efficient regulation.

After widespread immunization, major newspapers once again stopped covering open-air schools.

In academia, open-air schools have been defined as a “medical and pedagogical comet” that briefly crossed the sky of health and education, disappearing from sight in the mid-1950s.

But it is worth asking: is this comet destined to return to the public debate with every new health crisis for which there is no vaccine, only to disappear again into the immensity of historical oblivion?

Another common saying is that the open-air school movement was a “fruitful failure.”

A “failure” due to the fact that they remained marginal in education systems and were unable to become a universally adopted approach, as desired by many of their founders.

And “fruitful” because its principles have influenced teaching and school architecture to such an extent that they are no longer recognized as the fruit of outdoor experiences.

Another question we should therefore be asking is whether this fruitful failure represents an opportunity to rethink health and education not only in emergency situations, but to transform schools into healthier environments that promote good health.

For now, these questions remain unanswered.

André Dalben has a master’s degree in physical education and a PhD in Education from the University of Campinas (UNICAMP), and a postdoctorate in history from the Pontifical Catholic University of São Paulo (PUC-SP). He is a professor at the Institute of Health and Society of the Federal University of São Paulo (UNIFESP), Baixada Santista Campus.

Opinion articles do not necessarily reflect the views of Science Arena or Hospital Israelita Albert Einstein.

*

This article may be republished online under the CC-BY-NC-ND Creative Commons license.

The text must not be edited and the author(s) and source (Science Arena) must be credited.