#News

#News

Fertile science on the frozen continent

Scientists brave the freezing temperatures and rough seas of Antarctica in search of discoveries that could benefit human health

Bruna Martins/Estúdio Voador

Bruna Martins/Estúdio Voador

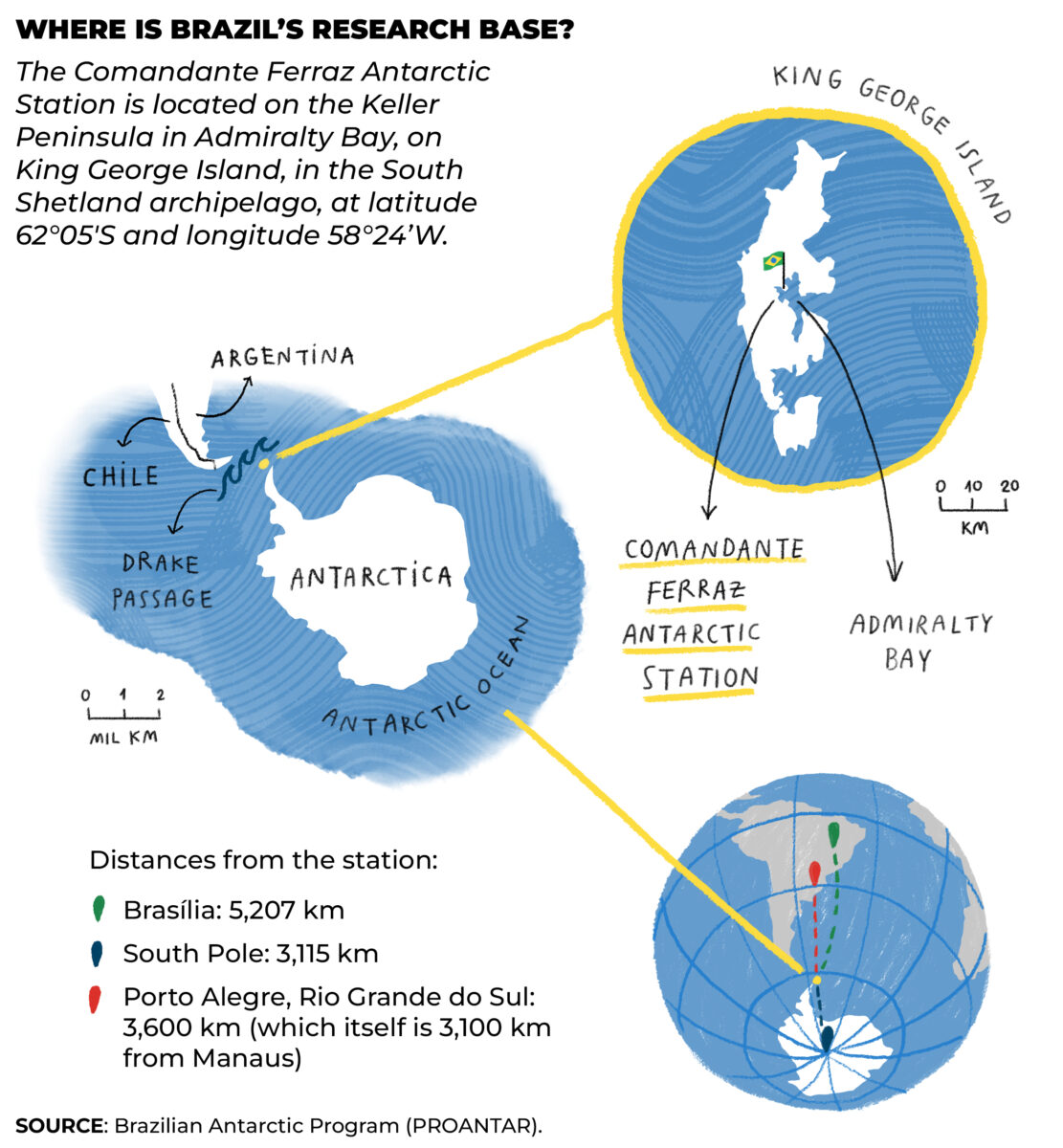

Although the Comandante Ferraz Antarctic Station on King George Island is only just beyond the halfway point between the southernmost Brazilian state of Porto Alegre and the South Pole, the dozens of scientists, technicians, and military personnel who travel to Antarctica every year face isolation and extreme temperatures on ships and at the Brazilian scientific base on the icy continent.

It is all made worthwhile by the visual and emotional impact of the local fauna and the wonder of the surreal landscapes that can be seen from the tiny point in Admiralty Bay where the Brazilian flag flies. Days of intense work on water and ice or in laboratories require not only meticulous preparation, but also rigorous physical and mental discipline, especially during the summer months, when the Brazilian research season is in full swing and the work is practically nonstop.

In the summer, which falls between December and February, it never gets completely dark—the sun shines for almost 24 hours a day, with the exception of just a few hours of continuous dusk. In the winter, when only a few researchers remain at the station due to the even greater logistical complexities, the opposite occurs: King George Island barely sees any daylight.

“It is due to the extreme characteristics of Antarctica that we decided to do a study there focused on human physiology and medicine,” says Dr. Rosa Maria Esteves Arantes, a professor from the Department of General Pathology of the Institute of Biological Sciences at the Federal University of Minas Gerais (UFMG).

For more than 10 years, the group led by Arantes has been surveying the health status of military personnel and civilians working in Antarctica. One of the objectives, she says, is to understand how the body responds to the low temperatures in the region.

She notes that the group’s field studies have faced two major hurdles: when the station was destroyed in a fire in February 2012, and when the COVID-19 pandemic began in March 2020, just two months after it was reopened. “In both situations, we had to formulate specific protocols for working there.”

In addition to her medical degree, which she completed in the 1980s, Arantes qualified as an anthropologist in 2017. “Antarctica fascinates me. It is important to understand how the human body responds to this extreme environment from a physical, mental, and social point of view,” says the scientist, highlighting the importance of understanding how anthropology can contribute to research on well-being and recovery in different places and cultures.

Logistical challenges

The geographic barriers imposed by the terrain create significant logistical obstacles for researchers. The Brazilian station is close to several bases of other countries, all located on the same archipelago. To get there by air, Brazilian Air Force planes have to land in the region via the airdrome run by Chile.

After landing on the Chilean runway, it takes a few more hours by boat to reach the Comandante Ferraz station. And when the runway is occasionally closed due to technical problems, the only way to reach Admiralty Bay is by ship.

“I was there a few months ago. We arrived at the station aboard the Almirante Maximiano research ship,” says Thiago Teixeira Mendes, a professor of physical education at the School of Education of the Federal University of Bahia (UFBA). The researcher was returning to the Comandante Ferraz Antarctic Station to collect samples that he had previously been unable to obtain because of the pandemic.

The Almirante Maximiano, part of the Brazilian Navy fleet, was acquired in 2009 with funding from Brazil’s Ministry of Science, Technology, and Innovation (MCTI). The vessel has three onboard research laboratories, equipment such as an oceanographic winch (for collecting water samples from up to 8,000 meters deep), and capacity for more than one hundred passengers.

The biggest challenge of the journey is usually Drake Passage, a stretch of sea between the Antarctic Peninsula and the southern tip of South America. The conditions in this maritime region are extremely complex, with winds that can exceed 100 kilometers per hour (Km/h), low visibility, and strong currents. All of these elements tend to result in very rough seas.

Researchers who frequently take part in the Brazilian Antarctic Program (PROANTAR) almost always have stories to tell about their journey to the Comandante Ferraz base by sea. It is not uncommon to hear reports of people tying themselves to their beds at night to avoid falling out due to the rocking of the ship.

The voyage is frequently canceled at the last minute, to the great dismay of everyone already on board. As it happens, one of the aspects to be assessed in the research project led by Mendes is the physical and mental exhaustion of people who spend up to six months confined on polar vessels.

“In our study, which is still ongoing, we are realizing the importance of regular physical exercise both before and during the journey on the ship, which is equipped with a gym,” explains Mendes. “We are looking at hormonal, immunological, and metabolic variables associated with stress and changes in circadian rhythms, which define sleep and hunger schedules. Living on a polar ship is itself a situation of isolation in an extreme environment.”

In search of microbial life

Another initiative studying health in Antarctica is the FioAntar Project, led by the Oswaldo Cruz Foundation (FIOCRUZ) as part of PROANTAR since 2019. Its objective is to identify disease-causing microorganisms on the continent with biotechnological potential.

One study by the FIOCRUZ scientists detected the presence of the H11N2 influenza virus, a subtype of the influenza A virus, in penguins on the South Shetland Islands in Antarctica. The discovery, described in an article published in the journal Microbiology Spectrum last year, suggests continued circulation of H11N2 on the continent and “reinforces the need for continuous surveillance of avian influenza” in Antarctica.

In another study, described in the journal Emerging Infectious Diseases, FIOCRUZ researchers identified the fungus Histoplasma sp. in Antarctica for the first time. The fungus causes histoplasmosis, a disease that affects the lungs and can be fatal.

As well as investigating potential new pathogens, the FioAntar Project also carries out bioprospecting, with a focus on extremophiles—organisms that live in extreme environments. These organisms often have unique molecules and physiological or chemical traits that are not found anywhere else on the planet. The aim is to identify extremophiles that could potentially be used to develop new health products and technologies, such as drugs and inputs.

The diversity of microorganisms in Antarctica has long drawn the attention of researchers at Brazil’s National Institute of Cryosphere Science and Technology (INCT Criosfera), which is responsible for approximately 60% of Brazilian research in Antarctica. One of them is microbiologist Luiz Henrique Rosa, head of the Laboratory for Polar Microbiology and Tropical Connections (MicroPolar) at UFMG.

Rosa has been carrying out studies in the region for more than 10 years, collecting soil samples, sediments, rocks, and plants in an effort to learn more about the microorganisms and flora of Antarctica. In recent years, he has worked on isolating fungi from snow and soil in the search for potential new antibiotics, primarily to treat tropical diseases such as dengue and yellow fever.

“As some fungi living in Antarctica are both adapted to these extreme conditions and geographically isolated, they may possess novel or unusual metabolic pathways for the production of compounds with potential biotechnological applications in medicine, industry, and agriculture,” Rosa wrote in a chapter of the book Fungi of Antarctica, which he edited in 2019.

South Pole

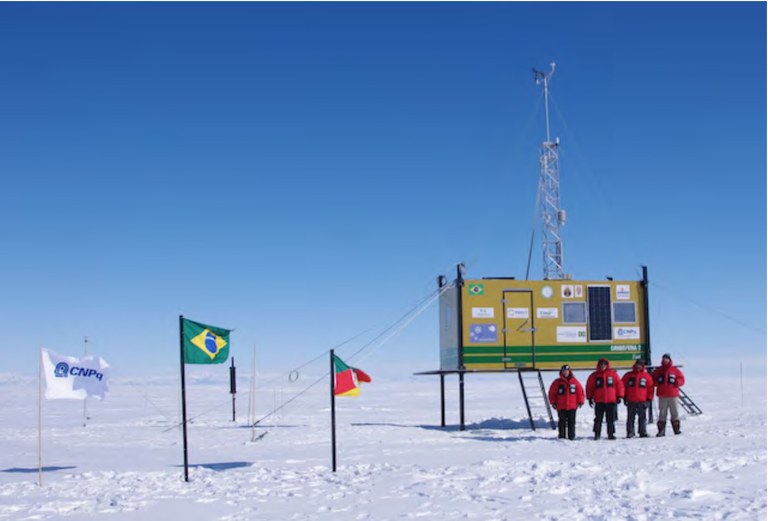

Brazil’s presence in Antarctica reaches far beyond the surroundings of the Comandante Ferraz station. Last summer, under the supervision of geologist and glaciologist Jefferson Cardia Simões, general coordinator of Brazil’s National Institute of Cryosphere Science and Technology (INCT Criosfera), which is responsible for around 60% of Brazil’s research in Antarctica, an expedition installed a Brazilian laboratory in the interior of the frozen continent, approximately 2,500 kilometers south of the main station.

The new Cryosphere 2 Scientific Module is situated in a region where the temperature averages minus 15 degrees Celsius and was installed by scientists from the Federal University of Rio Grande do Sul (UFRGS), the Federal University of Pará (UFPA), and Rio de Janeiro State University (UERJ).

The remote laboratory’s primary function is to complement the work of the first module (Cryosphere 1), recording meteorological data and levels of carbon dioxide (CO2)—the main greenhouse gas behind global warming and climate change, the effects of which include extreme heat, impacting human health.

Ice sample analyses, meanwhile, aim to contribute to our understanding of sea level changes. Holes have been drilled on the Pine Island Glacier, which has shown rapid changes over the past two decades.

Before leaving, Simões, who has been conducting research in Antarctica since 1991, described last summer as an important moment in Brazil’s Antarctic research. “Since the Brazilian station was reopened in January 2020, Cryosphere 2 was the first complete operation for which we fully utilized the station, something that was not possible while the COVID-19 restrictions were in place.”

The Comandante Ferraz station is now fully operational. “There are 17 laboratories where we can process our samples without having to take them to Brazil,” says biologist Paulo Câmara, a professor at the Department of Botany of the University of Brasília (UnB). “In the past, we used to lose many samples when transporting them to Brazil. And it gives us another interesting advantage: if things don’t go as planned, we can go back into the field and collect new samples.”

Câmara leads studies on fungi found in Antarctica. “We investigated a fungus of the genus Mortierella that attacks plants and tried to understand whether its presence is rising or falling in the region,” explains the researcher. “We have also studied vegetation and the impacts of climate change, and we have created inventories of biodiversity and endangered species, always working on the interface between botany and ecology,” says Câmara.

Despite the advances, the UnB scientist emphasizes that there are many challenges still to overcome to ensure that research in Antarctica continues. “One of them is to guarantee funding for the projects. In recent years, there has been financial instability and budget cuts for Brazilian research, which has impacted what we do on the icy continent.”

*

This article may be republished online under the CC-BY-NC-ND Creative Commons license.

The text must not be edited and the author(s) and source (Science Arena) must be credited.