#Columns

#Columns

Invisible state: How government contracts created Boston Dynamics

Public funding for technological development should not stem from private interests, but from the search for solutions to specific societal challenges

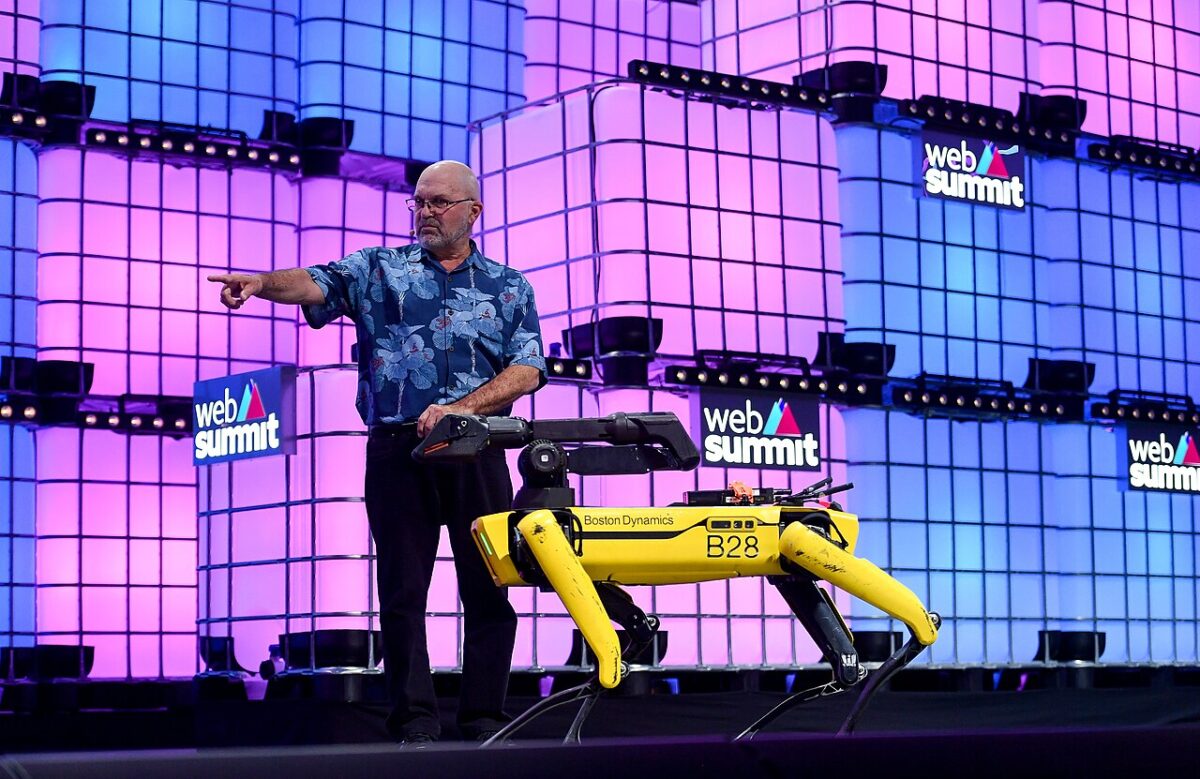

Engineer Marc Raibert, founder of the American company Boston Dynamics, with Spot, one of the company’s robots | Image: Web Summit / Wikimedia Commons

Engineer Marc Raibert, founder of the American company Boston Dynamics, with Spot, one of the company’s robots | Image: Web Summit / Wikimedia Commons

Capitalist companies introducing new things—innovations—to the market have to make investments that are complex, costly, and above all uncertain, both technologically and commercially.

As a result, they are often reluctant to do so.

The problem is that under capitalism, private businesses are the ones responsible for producing goods and services that in many cases allow us live longer and better lives. Hence the need for public support for innovation, even though the underlying strategies remain essentially private.

In recent years, this support has taken various forms, with the government awarding research and development funding, subsidized credit, and nonrefundable grants. These are the most traditional and passive forms of financial support.

Passive, because these public instruments are designed and implemented to sustain projects that serve a company’s own interests.

They do very well at lowering the opportunity costs of innovation, but they are not suited to solving major social problems or meeting specific public demands, especially when the market has no incentive to address them.

The issue is that their guiding paradigm is based on technical and scientific excellence in research, development, and innovation, not on the pursuit of deliverables rigidly tied to a specific formal demand.

In other words, their objectives, incentives, and rules are intended to support projects that align with corporate strategy rather than the funder’s priorities.

Through these mechanisms, the government can at best influence and highlight technological areas and general problems, but never a defined objective. Nor do they allow the state to make large-scale use of the innovations it subsidizes.

An innovation funded by government credit, for example, cannot immediately be used to apply a solution to a concrete public problem. The entire standard procurement process must still run its course.

From credit, grants, and subsidies, commercial outcomes should be expected, but only in the medium to long term, and entirely oriented toward the commercial developer’s interests.

Specific objectives

Countries like the USA and China have already realized that to quickly generate rapid traction in technology development projects, the funder (in this case the state) needs mechanisms that give it complete control—not over how research, development, and innovation (RD&I) activities are carried out, but over what problem they are meant to solve.

These countries, as well as the European Union, use contracts for RD&I services as a tool to promote innovation and solve complex problems.

Contracts for RD&I services contain specific clauses and regulations designed to make technological development a means, not an end.

They are therefore not only governed by innovation laws, but also by public procurement rules related to tenders and exemptions.

In these contracts, the private and public strategies converge in a positive dialogue; both parties, operating from different perspectives, work together in pursuit of a specific solution to a specific problem.

To this end, research alone is not enough, no matter how good it is. It is essential to achieve the designated objective, regardless of the technological complexity.

In my July 2024 column, I addressed these issues and described how in Brazil, RD&I contracts are known as technological orders and represent more than what the most disparaging might dismiss as a mere technicality. On the contrary, they subvert the linear, supply-driven approach by prioritizing public demand in the process.

In that piece, I only gave a few superficial examples.

Here, I will go into a little more detail about Boston Dynamics and how this prestigious American robotics company was created from RD&I contracts, and not research grants, subsidized credit, or nonrepayable funding.

Government contracts

For more than a decade, viral videos of robots such as Spot, which resembles a dog, or Atlas, which performs manual tasks better than I can, have left viewers speechless. These machines make a mockery of our slow process of evolution from the African savanna, straying into what was once the preserve of science fiction.

However, behind the hydraulic muscles, sophisticated sensors, and impressive balance is an element invisible to most: the government contract.

Boston Dynamics, now recognized as a global leader in robotics, began in academia—first at Carnegie Mellon University, then at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT).

The company flourished thanks to direct funding from the US Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA), created in 1958 in response to the former Soviet Union’s technological advances, especially the launch of the Sputnik satellite the previous year.

The rise of Boston Dynamics to a global leader in robotics owed little to venture capital rounds, accelerators, or IPOs—it was almost entirely due to government contracts. It was public demand that sustained the company’s technological progress.

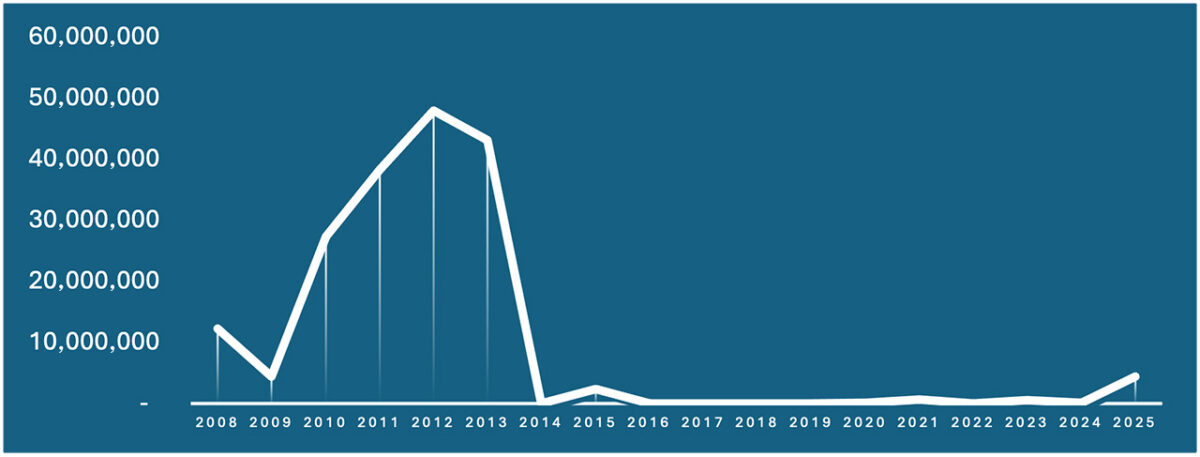

The graph below shows the funding received by Boston Dynamics through 57 contracts with the US government between 2008 and February 2025—21 of which were for R&D services—totaling almost US$200 million at 2025 values.

This figure, however, pales in comparison to some companies, such as Lockheed Martin and Boeing, which have received tens of billions of dollars through government contracts.

Funding for Boston Dynamics through US federal government contracts, 2008 – February 2025 (US$ at 2025 values)

A noisy dog

BigDog, the quadrupedal robot that made Boston Dynamics famous, was commissioned by DARPA with a very clear objective: to help soldiers carry equipment across hostile terrain.

The contract, signed in the early 2000s, paid out in stages: research, development, prototyping, and field testing. Each phase was tied to precise technical requirements with clear technical goals: autonomy, load capacity, balance, and responsiveness to commands.

This was not federal funding for generic technological development guided by the company’s market strategy. It was targeted at finding a solution to a specific challenge on the battlefield.

Either a useful technological development would be found or the project would be abandoned.

The BigDog was never used in real combat. It was too noisy. But as with any high-risk R&D project, its value was not only in the product, but in the learning curve.

Those who assume robot soldiers remain a distant prospect and that government contracts are slow to bear fruit should note that they are the origin of today’s most advanced commercial robots.

Without all the government contracts that allowed for the development of BigDog, there would be no Atlas, another robot created by the company. And it does not end there.

The extremely high-level demand from the state was the main reason Boston Dynamics was able to survive in its difficult early years. Interesting, is it not?

The government requests a highly uncertain technology; the project falls short of its actual objective, but the process gives rise to an entire line of robots embraced by the market.

The state could almost be called a “catalyst of the impossible” (pretty corny, I know). And, throughout the process, an externally innovative and disruptive company is fostered.

The accumulated knowledge paved the way for quieter, more robust and efficient robots. Spot and Atlas are, in effect, BigDog’s descendants.

This impressive evolution, which began with One-Leg Hooper while the team was still at Carnegie Mellon and MIT, is directly linked to a set of very specific demands translated into contracts with clear objectives.

What was the most decisive factor in this rapid technological evolution?

With government contracts, while the private company attempts to find a solution that does not yet exist, the state assumes most of the technological risk (or rather, pure uncertainty), and that is a great incentive, even when private sector interest is smaller.

This incentive can be so rewarding that it actually ensures a company’s survival in the early stages of its growth.

These contracts allowed Boston Dynamics to maintain the intellectual property, as established in US law under the Bayh-Dole Act, and use the accumulated know-how to develop commercial versions of the robots. The US government, meanwhile, retained the licensing rights and strategic knowledge.

This type of contract accelerates and directs technological progress, producing rapid responses that ultimately lead to socially useful applications, while also ensuring the survival of companies whose disruptive products would otherwise face a lack of immediate demand.

Driving technological change through serendipity (accidental discoveries) is crucial to the success of innovation systems, but it is not always the best way to tackle real-world problems.

In Brazil, we need to put more effort into targeted solutions. We cannot depend on the generic—albeit important—approaches of credit, subsidies, research grants, and university-business partnerships.

It is no coincidence that Petrobras (our “NASA”) is a leader in deepwater exploration: it got there by contracting research, development, and innovation services.

And I never tire of reminding readers that it was such contracts that led to the AstraZeneca vaccine and the Brazilian Air Force’s KC-390 aircraft. Through this type of contract, it is the end user’s needs that dictates the entire process.

The best thing about all this is that the state’s purchasing power is used to keep highly innovative companies alive during their most critical moments, allowing them to go on to become global technology leaders, as was the case with Boston Dynamics.

André Tortato Rauen is an economist with a PhD in science & technology policy from the University of Campinas (UNICAMP), currently a professor at the College of the Federal Public Audit Office (TCU). He is also a special advisor to the Brazilian Industrial Development Agency (ABDI).

Opinion articles do not necessarily reflect the views of Science Arena or Hospital Israelita Albert Einstein.

*

This article may be republished online under the CC-BY-NC-ND Creative Commons license.

The text must not be edited and the author(s) and source (Science Arena) must be credited.