#Columns

#Columns

We need to steer technological change

The innovations we need cannot depend solely on spontaneous discoveries prompted by curiosity

Footprint of American Buzz Aldrin, one of the first Apollo 11 astronauts to set foot on the Moon in 1969 | Image: Shutterstock

Footprint of American Buzz Aldrin, one of the first Apollo 11 astronauts to set foot on the Moon in 1969 | Image: Shutterstock

The great challenges of our generation—and of course I’m talking about climate change and how we treat our third rock from the Sun—have highlighted the need for humanity to produce and deploy a new wave of innovations that will allow us to develop economically without destroying what is left of the planet.

The problem is that time is running out. That is why we can’t depend on the important, but slow, transformation of scientific curiosity into concrete solutions. This linear model, which allows Big Science to create the knowledge base on which contemporary capitalist societies rely, is too diffuse for this moment. We need to accelerate, interact, test, and above all, steer.

This is precisely why we, technology economists, have changed our approach to public intervention in science, technology, and innovation. We have begun organizing these interventions based on problems we need to solve, rather than on what is already possible from a technological point of view.

For this reason, we began talking about mission-based policies and revisited the teachings of the impressive Apollo Program, which put “Man” on the Moon in an astonishing eight years.

Led by Italian American economist Mariana Mazzucato, this is what the developed world is doing right now.

One of her latest books, Mission Economy: A Moonshot Guide to Changing Capitalism, is a true ode to the human ability to solve problems through technological development coordinated by the government.

But it’s not easy to implement this type of intervention in the economy, especially in periphery countries.

This kind of approach, based on concrete demand, requires a comprehensive change in the public and private development system.

Assistance, which used to be segmented by scientific area, is now derived from the effective application of solutions. Additionally, command and control relationships, which were based around the scientific community, have changed.

The potential user gains greater prominence, and those who produce new knowledge are organized according to application.

This means that scientific and technological development must now be effectively managed and coordinated by a highly qualified technical team that can correctly translate the scientific and market perspectives. This is neither trivial nor common in public officials around the world.

In fact, the Apollo Program’s success was not just the result of the amount of money invested, nor the geopolitical pressure at the time.

What the Americans had, and still have, are good science and technology managers who have a solid academic background, corporate experience, and knowledge of public sector dynamics.

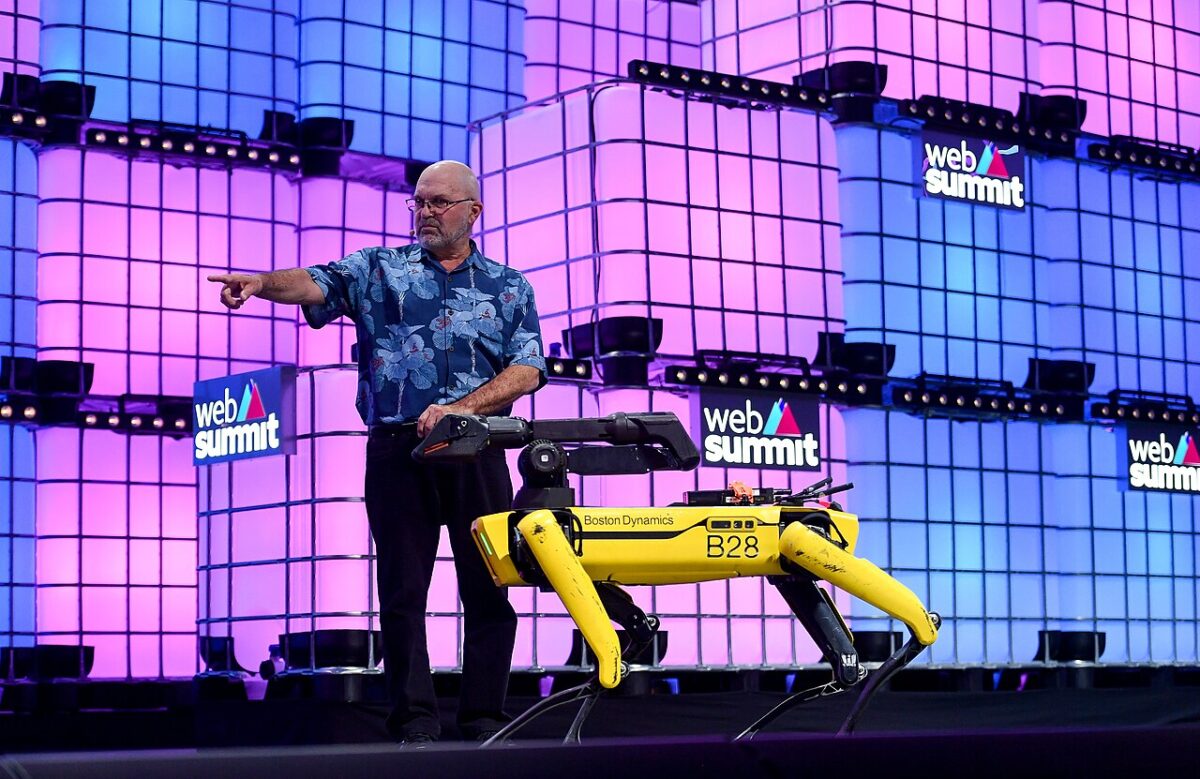

Professionals are responsible for the success of the DARPA (Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency) Model, which gave us GPS, the Internet, and Boston Dynamics and its dancing robots.

In relation to this incredibly important institution, I suggest reading The Pentagon’s Brain: An Uncensored History of DARPA, America’s Top-Secret Military Research Agency, by Annie Jacobsen.

At the end of the day, this is what’s important: when we start to promote science and technology with the goal of solving concrete, specific, and socially relevant problems, we need a type of professional that we don’t yet have on a large scale, neither in Brazil nor in the world. This professional is called the manager of science, technology, and innovation policies or actions. Historically, this position has been filled by notorious scientists who knew a lot about their scientific fields, but little about market logic and the way the public sector works, with its multiannual budget, demand for control and compliance, as well as concrete social impact.

The success of public intervention in ST&I in the 21st century will not only depend on the amount of resources available, but also on the quality of the professionals who plan, execute, and evaluate these interventions.

This is because, in the past, the scale of the problems and the way technological development was addressed—always in a linear fashion—allowed for subjective and diffuse organization. At the dawn of a new century, concrete reality is imposing itself, and it is necessary to steer and catalyze.

Professional certification

That is why the recent creation of the Innovation Institute, an initiative in which I am involved but which also includes Brazil’s most active players in the field, is so important.

It is a nonprofit organization with no party affiliations, which was created by the community of practice along the lines of the Project Management Institute (PMI), and it is designed to certify professionals who promote science, technology, and innovation in Brazil.

The idea here is to ensure that the complexity of the subject under development is reflected in the quality of the professionals working on it.

Regardless of the existence or lack of certifying institutions, the essential fact is that the volume and speed of innovations we need at this time in history cannot depend solely on spontaneous discoveries prompted by curiosity. It is clear that this approach—based on curiosity—must continue to exist, because otherwise we wouldn’t have a scientific basis to build upon. However, only the professional and targeted treatment of public and private resources for ST&I can get us out of the environmental mess we’re in.

André Tortato Rauen is an economist with a PhD in science & technology policy from the University of Campinas (UNICAMP), currently a professor at the College of the Federal Public Audit Office (TCU). He is also a special advisor to the Brazilian Industrial Development Agency (ABDI).

*

This article may be republished online under the CC-BY-NC-ND Creative Commons license.

The text must not be edited and the author(s) and source (Science Arena) must be credited.