#News

#News

Polio: why we cannot let our guard down

The virus could yet reemerge in Brazil, despite a slight improvement in vaccination coverage

Once internationally renowned for its vaccination programs, Brazil is now facing the possibility of polio returning | Photograph: Fernando Frazão/Agência Brasil

Once internationally renowned for its vaccination programs, Brazil is now facing the possibility of polio returning | Photograph: Fernando Frazão/Agência Brasil

For a long time, Brazil was globally renowned for its high vaccination coverage. Thanks to its highly successful National Immunization Program (PNI), created in 1973, the country managed to eliminate and control several vaccine-preventable diseases in recent decades, including measles, diphtheria, and polio. In total, more than 20 vaccines are offered free of charge by the country’s National Health System (SUS), of which 17 are for children, according to the Brazilian Ministry of Health. With the introduction of the polio vaccine, the Americas were named the first region in the world to eradicate the disease in 1994.

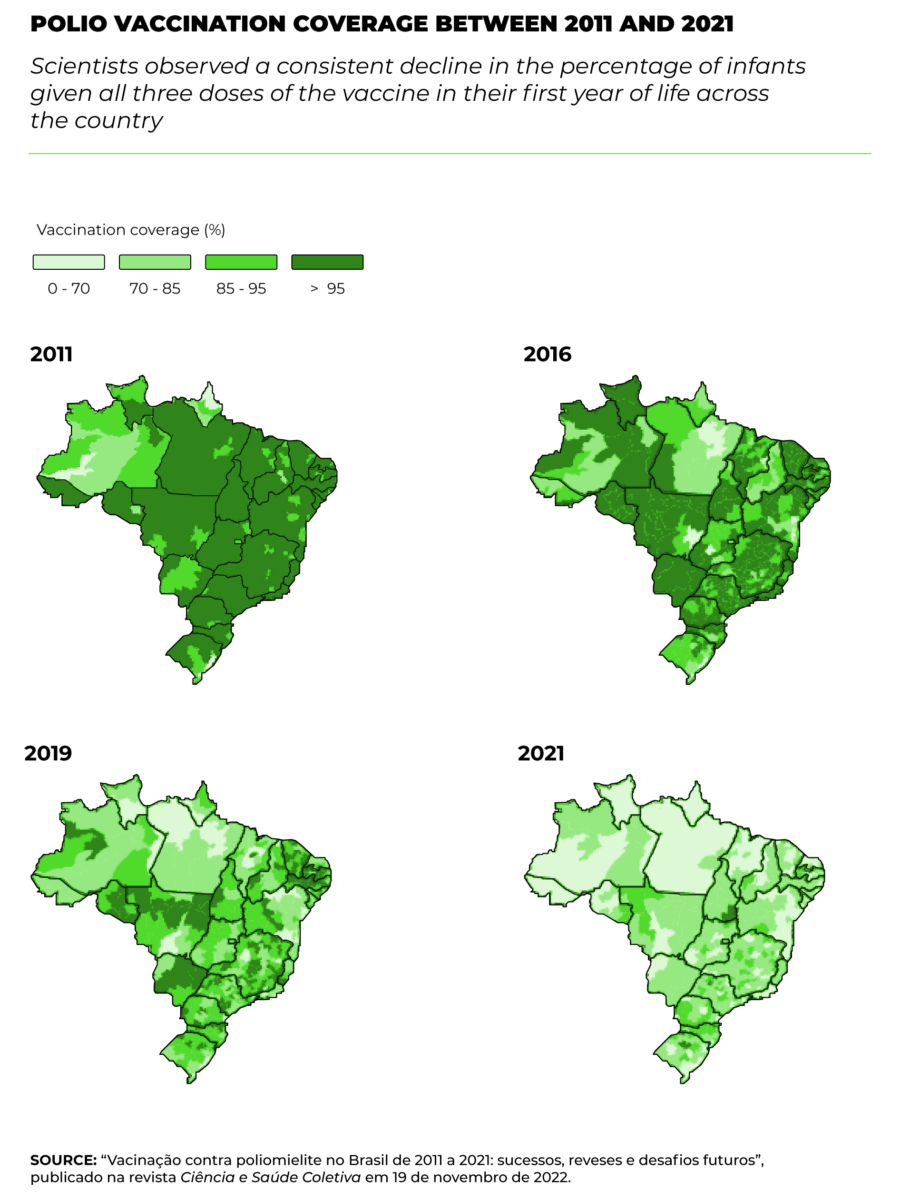

The situation, however, has changed greatly over recent years. Vaccination coverage in Brazil and worldwide has suffered a significant drop. A study published in the journal Ciência & Saúde Coletiva by scientists from several Brazilian universities warned about the seriousness of the decline in childhood polio vaccination, emphasizing the imminent risk of the virus being reintroduced and once again circulating in Brazil if the rise in vaccination uptake observed at the end of 2023 does not continue.

The authors analyzed official PNI data from 2011 to 2021, finding that the drop in vaccination coverage was greatest in the North and Northeast of Brazil—two of the country’s poorest and most unequal regions.

According to the study, almost half of Brazil’s states had an estimated polio vaccination rate of 100% in 2011. Ten years later, however, this feat was not achieved by a single state.

According to the Ministry of Health, 74% of Brazilians were inoculated against polio in 2023, up from 67.1% in 2022. Although there are signs that the country has begun to reverse its downward trend, the recovery is still not as pronounced as has been observed with other vaccines, such as the BCG (for tuberculosis), which is the only vaccine that has reached the target set by the government.

“The figures released by the Ministry of Health are excellent news,” said epidemiologist Maria Rita Donalisio, a professor at the School of Medical Sciences of the University of Campinas (FCM-UNICAMP) and lead author of the article published in Ciência & Saúde Coletiva.

She stresses, however, that there is still a real risk of polio reemerging in Brazil. “We have not reached the ideal polio vaccination rate of 95%. There is a lot to be done, especially because we still have to contend with people visiting from other countries where the virus is circulating, and visiting areas where the population is unprotected.”

The study led by Donalisio and her team shows that Amapá, Roraima, Acre, Rondônia, Ceará, Paraíba, and Pernambuco are the states with the biggest drops in vaccination coverage in the analyzed period of 2011 to 2021 (see graph). Of these, the biggest decline was observed in Roraima (almost 15%).

The polio vaccination decline in the North and Northeast was more pronounced from 2020 onwards due to the COVID-19 pandemic. One after another, states began falling short of the 95% vaccination rate previously achieved in much of the country. “The 95% target reached in most regions in 2011 was largely missed in 2021.”

With a slight recovery in 2022 and 2023, the Northeast recorded the largest increase in coverage for all three doses of the polio vaccine, reaching almost 68%, as reported by the Child Health Observatory.

“We can see that the Ministry of Health is currently very committed to increasing polio vaccine coverage. That does not mean, however, that epidemiological surveillance agencies or the public should let their guard down,” says Donalisio.

Health regions

The researchers used interrupted time series analysis with immunization data from the PNI Information System (SI-PNI/DataSUS) to analyze the downward trend in vaccination between 2011 and 2021. They also investigated the impact on the PNI of the restrictions implemented during the pandemic.

The group then used the Brazilian Deprivation Index (IBP)—created by the Oswaldo Cruz Foundation (FIOCRUZ) and the University of Glasgow, Scotland—to measure the socioeconomic conditions of different municipalities, establishing a relationship between economic and social vulnerability and the decline in vaccination coverage.

This comprehensive data set was used to perform a spatial analysis of polio vaccination in Brazil’s 450 so-called health regions, formed by groups of neighboring municipalities that share cultural, economic, and social identities, communication networks, and transport infrastructure. The purpose of these regions is to facilitate the planning and implementation of health measures and services.

Health regions that once achieved vaccination rate targets of 95% gradually failed to do so over the years studied (2011, 2015, 2019, and 2021). In the North and Northeast, the majority of health regions had coverages of below 70% in 2019 and 2021.

Clusters of health regions with low coverage were mostly concentrated in the North of Brazil (see maps).

“It is extremely worrying that the polio virus is still endemic in Asian and African countries, such as Afghanistan and Nigeria, and that vaccination coverage has fallen in Brazil and worldwide in recent times,” says Donalisio.

As long as the virus is circulating in the population, she says, there will always be a chance of polio being reintroduced in places previously considered safe.

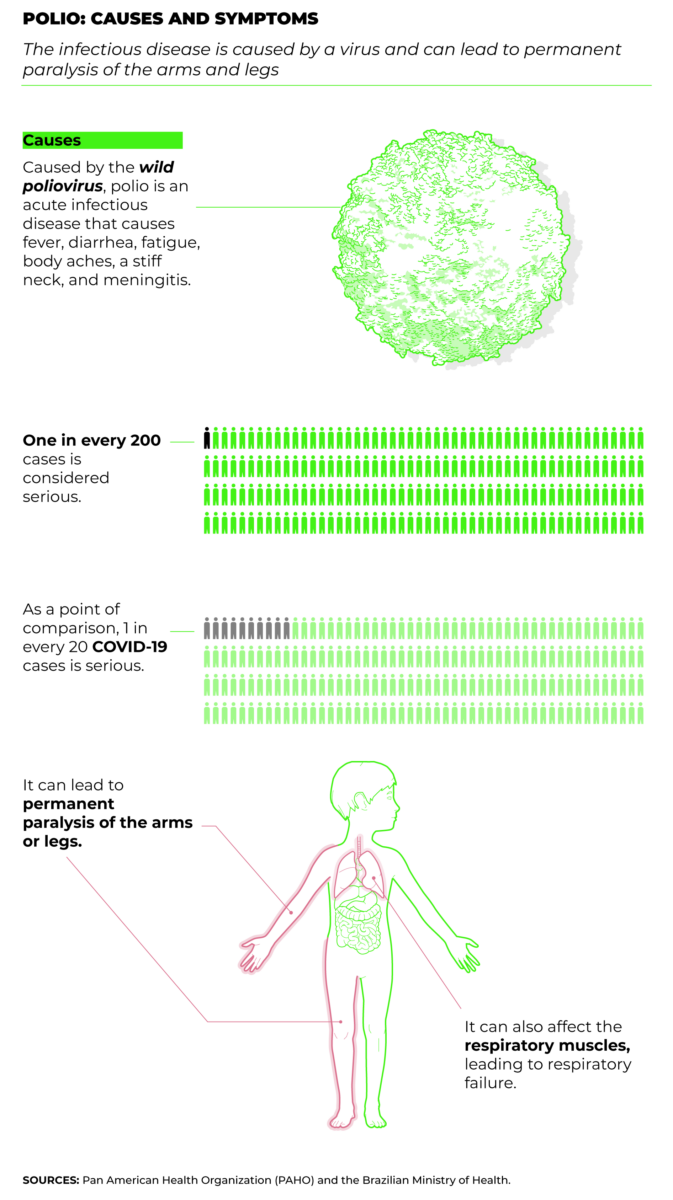

Donalisio also draws attention to the fact that immunosuppressed patients (with low natural defenses against pathogens) find it more difficult to resist infection. “The virus thus circulates quickly and can develop variants, although it is more stable than some viruses, like SARS-CoV-2, for example.”

Socioeconomic characteristics

The study identified the issue of socioeconomic inequality as one of the main factors behind the decline in vaccination coverage in Brazil and around the world. Donalisio names some of the factors behind the falling immunization rates in the country.

“In states like Roraima, Amapá, Paraíba, and Pernambuco, there are areas that are difficult to access—communities and villages that family health teams can only reach by boat,” highlights the scientist.

“To make matters worse, the spaces used to administer vaccines are often structurally inadequate, leaving health professionals overworked.” Donalisio points out that problems with SUS funding and governance also present obstacles. “There is no drive to train more staff to apply vaccines or to intensify immunization campaigns in the interior of the country.”

Another challenge is improving communication about the importance and complexity of vaccination. “Vaccination schedules have become more robust and complicated in recent years,” says the UNICAMP researcher.

“It includes various doses for vaccines such as the pentavalent vaccine [for diphtheria, tetanus, whooping cough, hepatitis B, and hemophilia B, which causes meningitis and other diseases], the BCG [for tuberculosis] and the MMR [for measles, mumps, and rubella],” she explains.

“This is great, but at the same time it requires assertive and effective dissemination of vaccine schedules for children, adolescents, adults, and pregnant women,” says Donalisio.

It is also necessary to ensure proper management of immunobiologicals in the cold-chain during vaccine distribution. “Some products must be kept refrigerated, while others need to be kept frozen.”

When it comes to polio, the public seems to believe that the disease is no longer a threat, since its elimination from the country was announced such a long time ago.

“People do not really see the return of the disease as a concern,” points out Donalisio.

Measles is another disease that had been eradicated, but has now returned with force. “In 2016, Brazil was internationally certified as a measles-free nation. But since then, there have been outbreaks of this viral infection, which affects the immune system and can be fatal.”

A look at the past

With the threat of the wild poliovirus being reintroduced in Brazil looming, a look at the past may provide valuable insight into the crucial role public health efforts played in combating the disease throughout the twentieth century.

After first being recorded in the country at the end of the nineteenth century, polio caused numerous outbreaks before being classified as a major public health issue by the authorities.

“Polio was considered a mysterious disease that challenged doctors and scientists,” says Dilene Raimundo do Nascimento, a doctor and historian at FIOCRUZ in Rio de Janeiro. “Until the mid-twentieth century, scientists and medical professionals were unable to explain how the disease was transmitted.”

It was in the 1950s that polio caught the public’s attention, as outbreaks spread through several Brazilian cities. The largest epidemic ever recorded in the country occurred in Rio de Janeiro in 1953, resulting in major press coverage and public concern, which increased the pressure on doctors and the authorities to find a solution.

“At the same time, the quest to create a polio vaccine was making good progress, especially in the US,” says Nascimento, editor of História da poliomielite (The history of polio; Garamond, 2010), a book about the scientific, social, and political trajectory of the disease in Brazil and worldwide.

The efforts of the international scientific community in the 1950s resulted in the development of the two polio vaccines still in use today.

The first, which uses an inactivated version of the virus and is administered intravenously, was created by American epidemiologist Dr. Jonas Salk (1914–1995). The second, produced with a live but attenuated virus and given orally, was developed by Polish medical researcher Dr. Albert Sabin (1906–1993).

Thanks to these vaccinations, the disease disappeared in many countries by the early 1960s. In Brazil, however, much of the population remained unprotected due to difficulties accessing medical services and vaccines.

“For health managers and professionals, the biggest challenge was to establish partnerships between multiple institutional and social stakeholders,” says Nascimento.

First nationwide campaign

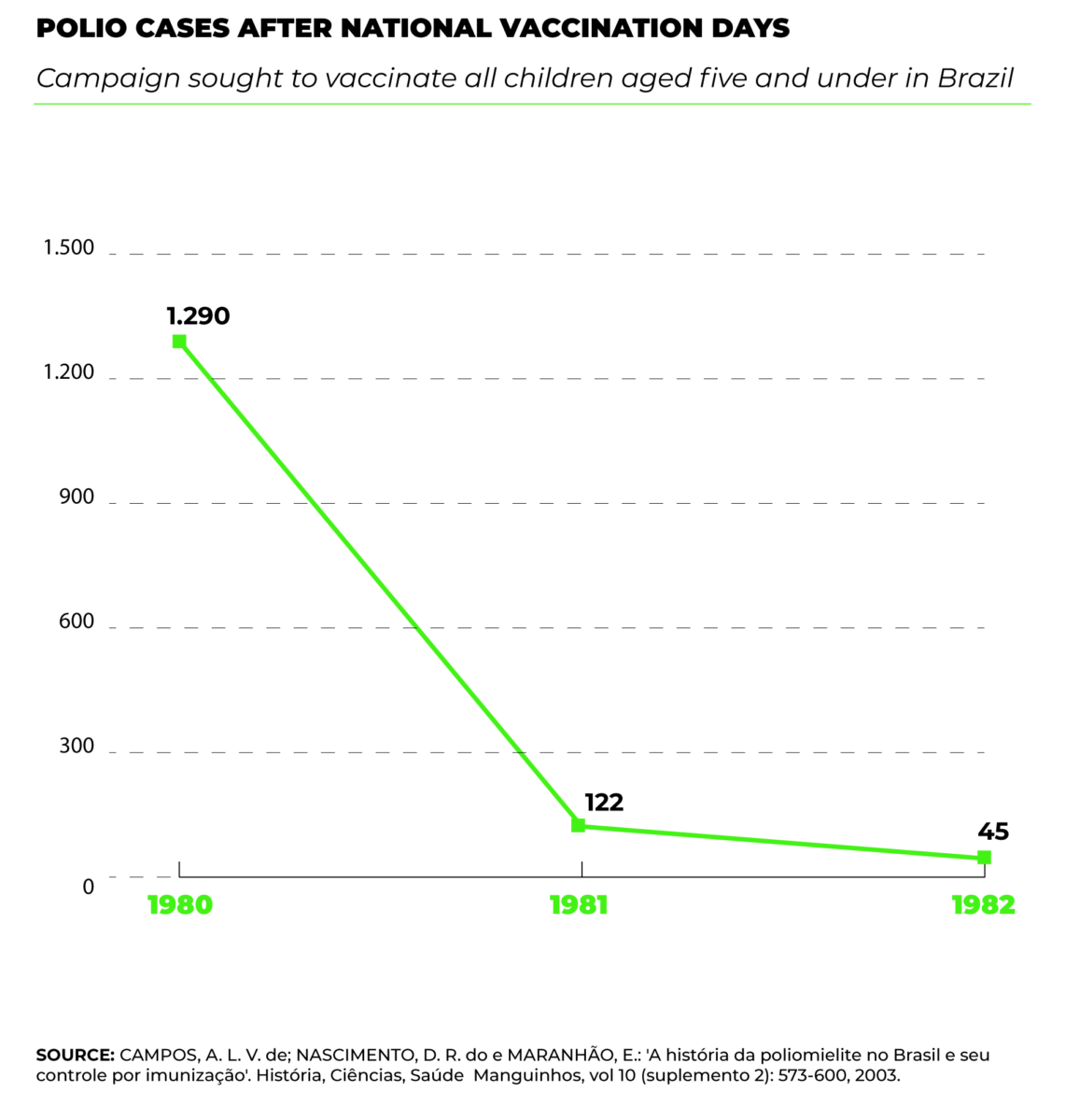

Mass immunization drives were implemented in the 1960s and 1970s, but without the scope and longevity needed to contain the spread of polio. It was only in the 1980s that Brazil established its first nationwide immunization campaign.

“The outbreak of a major polio epidemic in Paraná and Santa Catarina drew national attention to the issue in late 1979 and early 1980. The political and social landscape at that time were also favorable to fighting polio in the country,” says Nascimento, referring to the fact that the military regime in charge at the time (1964–1985) was facing a serious political and economic crisis that began during the General Ernesto Geisel administration (1974–1978).

In this period of rising social tensions, the dictatorship was seeking to appear a little less strict, and there was interest in using social policies to legitimize these changes.

‘National Vaccination Day’ was established, with the aim of vaccinating all children aged five and under across the country in a single day. There followed a sharp reduction in the number of cases of the disease, from 1,290 in 1980 to 122 in 1981. The following year, the lowest ever number of annual nationwide cases was recorded: 45.

According to Nascimento, these “national vaccination days” were warmly welcomed by the public, and they continue to be systematically implemented in Brazil to this day.

“The policy even went international, being recommended by the Pan American Health Organization [PAHO] as a model for interrupting the transmission of wild poliovirus in the Americas.”

Vaccination communication and culture

Both researchers report that there were serious shortfalls in communicating the importance of vaccines to the public. For FIOCRUZ’s Dilene do Nascimento, the success of the polio immunization campaign in the 1980s created a “culture of vaccination” among the public, with parents aware of the importance of taking their children to be vaccinated and keeping their vaccine records up to date.

However, she emphasizes that government campaigns are still needed to highlight the importance of immunization and inform people of when they can get vaccinated against different diseases—this is more important now than ever, with the rise of antivaccine groups and fake news on the subject.

The paper cited at the beginning of this article, which compared vaccination coverage in 2011 and 2021, noted that the fourteenth meeting of the Regional Certification Commission for Polio Eradication in the Region of the Americas classified the region as a high risk for the reintroduction of polio.

Against this backdrop, the government launched the National Response Plan for Poliovirus Detection and Polio Outbreaks in November 2022, with the objective of establishing guidelines on how to swiftly respond to cases of wild poliovirus or poliovirus derived from the disease, in addition to creating communication and surveillance strategies for types 1, 2, and 3 of the virus.

“The plan is greatly welcomed. We hope it will help restructure the vaccination program and reinforce health messaging and communication about vaccination campaigns for polio and other diseases,” says UNICAMP’s Maria Rita Donalisio.

“This could give us the boost we need to become a model of free and universal vaccination campaigns once again.”

Re-achieving high vaccination coverage

Nascimento cites a recent project by FIOCRUZ’s Institute of Immunobiological Technology (Bio-Manguinhos), the Brazilian Society of Immunizations (SBim), and Brazil’s National Immunization Program (PNI).

The Reattainment of High Vaccination Coverage (PRCV) initiative aims to reverse the decline in vaccination rates in Brazil.

It was started in 2021 in the state of Amapá and 25 municipalities in Paraíba (covering 11% of the state’s municipalities and 37% of its total population) due to low vaccination rates in the region, especially for diseases such as polio, measles, and rubella.

The results in these locations were encouraging. Between 2020 and 2021, both Paraíba and Amapá placed last in polio vaccination rates among children—in December 2022, after the vaccination campaign and other measures implemented by the project, they were the only two states in Brazil to hit the target of 95% vaccination coverage.

The aim is to increase vaccination coverage nationwide by 2025.

*

This article may be republished online under the CC-BY-NC-ND Creative Commons license.

The text must not be edited and the author(s) and source (Science Arena) must be credited.