#News

#News

Possible causes of cleft lip condition

Study indicates that inflammatory diseases of pregnancy may affect the regulation of genes involved in facial formation during fetal development

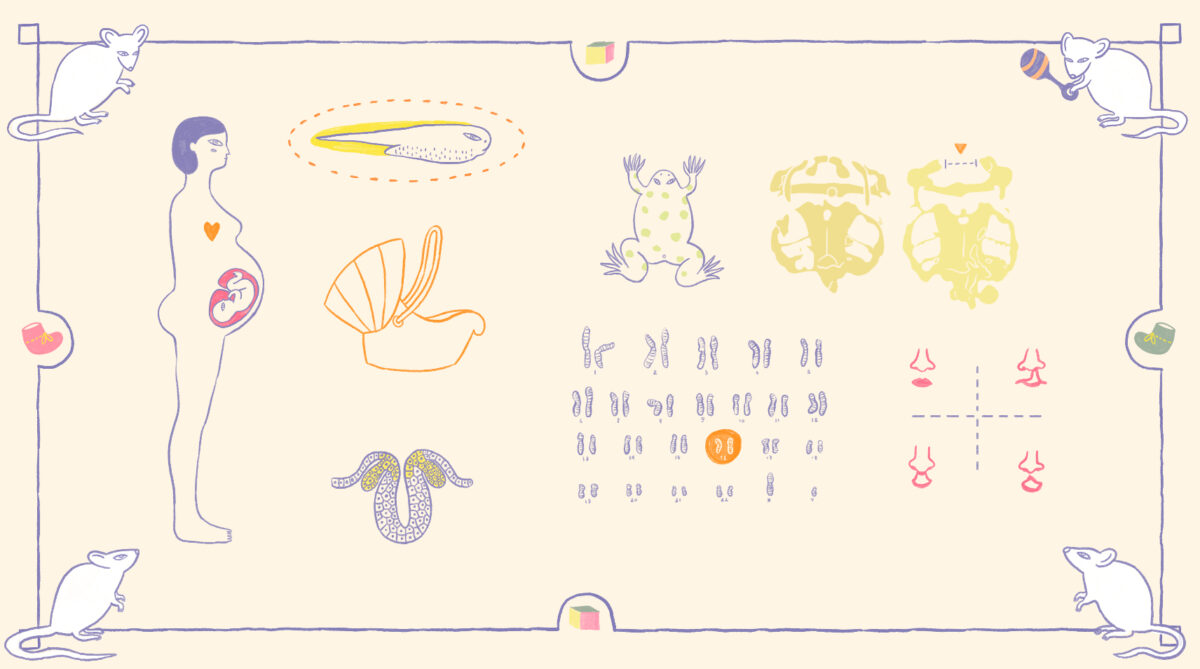

Illustration: Lívia Serri Francoio/Estúdio Voador

Illustration: Lívia Serri Francoio/Estúdio Voador

A study by the University of São Paulo (USP) and University College London demonstrated that cleft lip/palate—when the lip, palate, or both do not form properly—occurs during pregnancy in genetically predisposed fetuses exposed to inflammation caused by maternal illnesses such as diabetes and obesity. The study, published in the journal Nature Communications,showed that inflammation produces substances capable of inhibiting the CDH1 gene, reducing the production of a protein important to formation of the face.

“The CDH1 geneproduces a protein called E-cadherin, which promotes the migration of stem cells toward the facial region in the first weeks of fetal development, giving rise to the lips, mouth, nose, and other structures,” explains Maria Rita Passos-Bueno, a geneticist from the Center for Human Genome Studies at the University of São Paulo (CEGH-USP).

According to Passos-Bueno, inhibition of this gene by inflammation leads to a reduction of the stem cell migration speed. As a result, the cells fail to meet in the middle of the face and a cleft is thus formed.

According to Brazil´s Ministry of Health, cleft lip/palate affects 1 in 650 newborns in Brazil and is the second leading cause of death in the perinatal period, which extends from the twenty-second week of pregnancy to the seventh day after birth. The condition makes it difficult to suck and chew, as well as causing speech delays and impediments. The problem can be alleviated with surgery.

Passos-Bueno explains that if both copies of the CDH1 gene are mutated, the fetus becomes inviable. But if at least one of them functions—whether it is the one passed down from the father or from the mother—the fetus produces half of the normal level of E-cadherin.

The geneticist, who has been monitoring the families of patients with cleft lip/palate for two decades, already knew that the malformation occurs in about 50% of people with the mutated gene and that the severity of the cleft varies greatly from one patient to another. “I knew the mutated gene itself does not cause the malformation, which also depends on environmental factors. In addition, more severe inflammation can cause larger clefts,” she says.

“With half the E-cadherin, the fetus can develop normally, but inflammation seems to increase the risk,” says USP geneticist Passos-Bueno.

To confirm this hypothesis, the scientists applied inflammation modulators called cytokines, produced by genetically modified bacteria, to mice and frogs, as well as to in vitro human cells, some of which were genetically modified to carry the mutated CDH1 gene and others that were not.

In animals with the mutation exposed to cytokines, a cleft lip/palate was formed comparable to those seen in humans, and in human cells, stem cell migration decreased, confirming that both factors contribute to the formation of the cleft lip/palate.

When the cytokines were applied to animal and human tissue without the mutated gene, cell development and displacement were normal, indicating that inflammation alone does not cause the condition.

“The result confirmed the hypothesis that inflammation and the mutated CDH1 gene together produced the cleft,” explains Passos-Bueno. When the genes were normal, inflammation did not affect development. The molecular mechanisms involved remain to be investigated.

Epigenetic inhibition

The scientists conducted biochemical analyses of the mice, frogs, and in vitro human cells subjected to the cytokines and found a modification in the DNA region that regulates the CDH1 gene. The region had received a molecular signal, known as methylation, that inhibits the production of E-cadherin.

Methylation is an epigenetic mechanism of gene regulation, increasing or decreasing protein production without changing the letters of the DNA. It caused the normal gene, which was producing only 50% of the E-cadherins, to produce even less, leading to the risk of malformation.

“In humans, the mother’s cytokines probably pass through the placental barrier, leading to an epigenetic dysregulation of the CDH1 gene in the fetus,” theorizes Passos-Bueno. The scientists called the process a 2-hit model, comprising first the loss of function in one of the copies of the CDH1 gene and then the reduction of E-cadherin production by the remaining functional gene due to inflammation. Without enough protein, stem cell migration slows down, resulting in formation of the cleft.

“As far as I am aware, there are very few studies showing the molecular mechanisms that cause environmental factors to affect genes in human malformations,” says Karina Griese Oliveira, a geneticist at Hospital Israelita Albert Einstein who was not involved in the study.

Oliveira explains that epidemiological studies often indicate possible relationships between environmental and genetic factors, but without demonstrating the molecular mechanism involved to prove the link between cause and effect.

“The study clearly shows that the environmental factor of inflammation serves as a trigger in the formation of a cleft lip or palate in the fetus,” says Oliveira.

“Among all cases of cleft lip/palate, only 1% are caused by a CDH1 mutation,” emphasizes Passos-Bueno, who points out that there are other genes with a much smaller environmental influence, such as IRF6, which causes malformation in 90–95% of cases. However, CDH1 was chosen precisely because it allows scientists to better understand the interaction between genetic and environmental factors.

“There are many genes involved in the cleft lip, and in the future we want to see whether inflammation affects other genes that contribute to the malformation,” says Passos-Bueno.

The combination of CDH1 and inflammation is also related to gastric cancer, and the researcher plans to study whether the same 2-hit model may explain the development of this disease.

*

This article may be republished online under the CC-BY-NC-ND Creative Commons license.

The text must not be edited and the author(s) and source (Science Arena) must be credited.