#News

#News

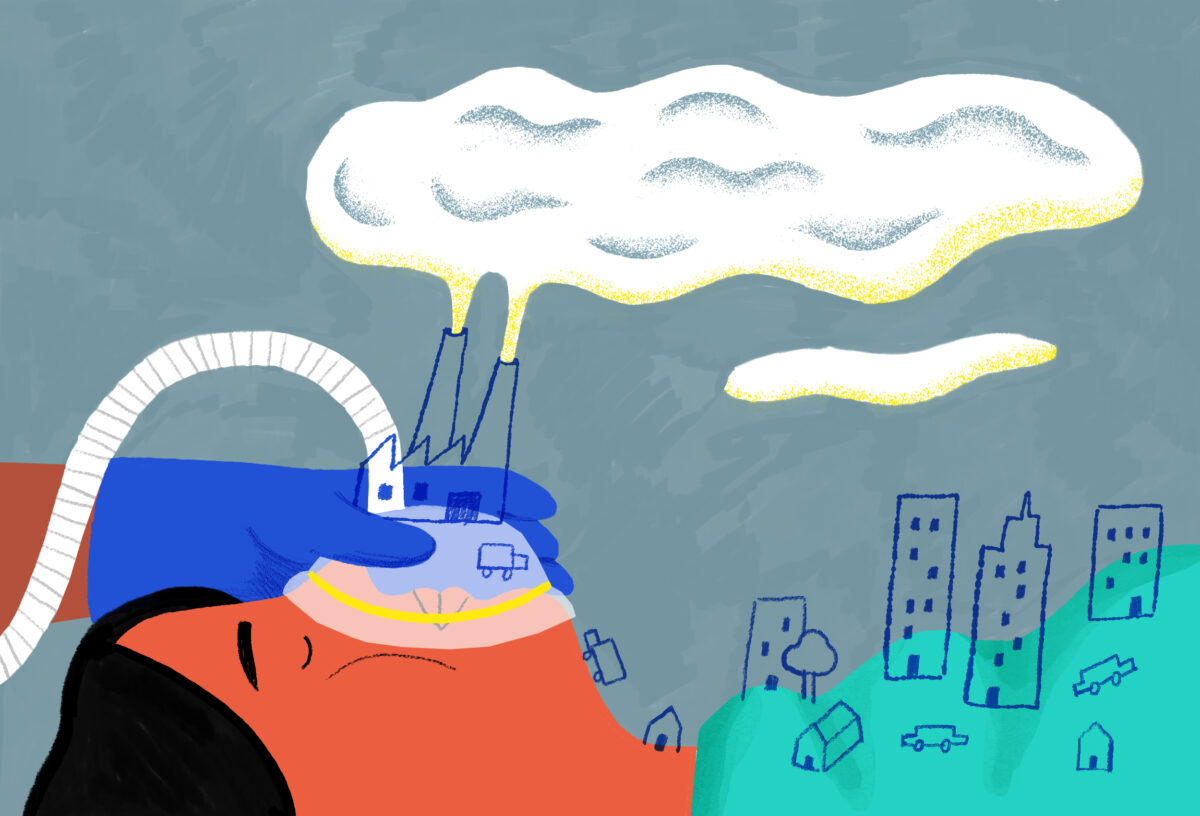

Inhalational and anesthetic gases worsen climate change

In countries such as the United States, healthcare is responsible for almost 9% of greenhouse gases

Illustrations: Bruna Martins/Estúdio Voador

Illustrations: Bruna Martins/Estúdio Voador

The United Kingdom’s National Health Service (NHS), the country’s public health system, announced earlier this year that the use of the anesthetic gas desflurane will be discontinued from 2024. The measure is aimed at reducing environmental impacts caused by the NHS. Amid growing concerns over the irreversibility of climate change, all segments of society have been concentrating their efforts into minimizing the problem—and the health sector is a significant contributor to the worsening climate crisis. Healthcare provision in the UK is responsible for almost 5% of greenhouse gas emissions, while the figure in the US is close to 9%.

Desflurane is an inhaled anesthetic commonly used prior to surgeries and was the first target of the NHS task force, given that its potential for impacting global warming is 2,500 times higher than that of carbon gas—public enemy number one for the greenhouse effect.

The alternative to desflurane is nitrous oxide, but its anesthetic effect is less powerful, so it needs to be used in higher concentrations. As a result, the environmental impacts of nitrous oxide are similar to those of desflurane, and it remains in the atmosphere for 114 years. One possible substitute for desflurane is the anesthetic sevoflurane, with 15 times less environmental impact.

In the UK, where there are large quantities of data available on the theme, it is known that anesthetic gases used during surgeries and in Intensive Care Units (ICUs) are responsible for 2% of all emissions. With the support of the Royal College of Anaesthetists and the Association of Anaesthetists, the NHS currently permits the use of desflurane only in very specific circumstances.

Measures such as those adopted in the UK can be observed in other countries. In 2022 the Department of Anesthesiology at the University of Michigan’s Faculty of Medicine in the US launched an initiative to promote “green anesthesia.” The aim is to find ways to reduce emissions generated by surgical centers. One way is to encourage more use of sevoflurane, according to a news piece published on the institution’s website. “Administration of sevoflurane for one hour has a similar environmental impact of driving a gasoline-fueled vehicle for 20 miles [32 kilometers], while one hour of desflurane is estimated at 400 miles [643 kilometers].”

The situation, however, is much more complex than it seems, and requires more comprehensive actions than just replacing one substance with another. This is made clear in a document published in 2021 by the World Federation of Societies of Anaesthesiologists (WFSA), with sustainable recommendations on the use of anesthetics.

According to the WFSA, ecologically correct medications and equipment should be favored when shown to be clinically safe options. The organization also recommends reducing excessive use of resources and for hospitals to mitigate wastage of medicines, water, and power. They also suggest including environmental sustainability as a research and training theme.

“Even though desflurane is not responsible for the highest carbon footprint caused by healthcare, this is a change that we can easily implement in the medical routine by making practical adjustments, with no adverse effect on patients,” explains Clifford Shelton, executive editor of the journal Anaesthesia Reports and a senior lecturer at the Lancaster University Medical School in the UK. “It is evident that going forward we need to think about the environmental impacts of medical practice as a whole.”

Shelton, who has been looking into the matter in recent years, exemplifies the ease of implementing change (such as that related to the use of desflurane) citing data from the national audit conducted every three years by the Royal College of Anaesthetists at UK hospitals. One of the latest editions found that the use of intravenous anesthesia in the country increased from 8% to 26% between 2013 and 2021. The technique has been recommended under sustainability guidelines since it can help reduce the use of inhalational substances.

Another reference in this debate is a guide published in June of last year by scientists from Australia and the US. This paper provides guidance on how institutions can deal with pollution caused by inhaled anesthetics and brings together consolidated evidence.

“Most of the recommendations are immediately applicable, and all can be implemented in a decade,” says Jodi Sherman, associate professor of anesthesiology at Yale University, USA, and one of the guide’s authors.

“Emissions from inhalational anesthetics will not be cut to zero but could be reduced by 90% if all the measures are followed,” says Sherman, who is also founder of the Healthcare Environmental Sustainability Program at Yale.

Internationally renowned in the field of sustainability in clinical care, Sherman draws attention to the complexity of the issue. “There are several factors involved when we talk about making clinical care more sustainable,” he says.

“There are measures aimed at reducing the use and waste of anesthetic gas, eliminating the use of desflurane and decommissioning nitrous oxide installations, which manage the gas cylinders. However, other actions are more burdensome, such as the use of intravenous anesthetics and the treatment of residual anesthetic gas”, says Sherman.

The researcher also highlights that, in addition to inhalational anesthetics, other medications need to be studied more closely in terms of their undesired environmental effects—including hydrofluoroalkane, used to treat respiratory diseases, particularly asthma. This gas is used as a propellant in inhalers and may contribute to the greenhouse effect.

Asthma

According to data from the Brazilian Society of Pulmonology and Phthisiology (SBPT), it is estimated that at least 300 million people suffer from asthma around the globe, and some 328 million have chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). Both are among the primary global causes of death.

Inhalation devices (known as “pumps”) significantly increase quality of life for patients, but most of these devices contain fluorinated gases, whose carbon footprint is considerable.

There are currently three main classes of device available:

- Pressurized metered-dose inhalers (pMDI);

- Dry powder inhalers (DPI);

- Soft mist inhalers (MSI).

“The carbon footprints of these devices are different, and more expressive with pMDIs. This means that new approaches need to be considered to balance environmental goals with patient health and well-being,” says physician Marilyn Urrutia-Pereira, a lecturer at the Federal University of Pampa (UNIPAMPA) in the state of Rio Grande do Sul and member of the Pollution Committee at the Latin American Society of Allergy, Asthma, and Immunology (SLAAI).

According to the researcher there are several possible alternatives, but it is still difficult to make precise comparisons between studies into carbon footprints due to the different methods used in analyses.

One simple way to reduce emissions is to encourage the use of dry powder inhalers, adds Urrutia-Pereira. “Patients who change their maintenance therapy from pMDI to DPI reduce their inhaler carbon footprint by more than half, without losing control over their asthma.” Soft mist inhalers produce aerosols from waterborne formulations and by the different nebulizer mechanisms, but they are still more expensive than pMDIs and DPIs.

Changing devices is obviously not an option for all patients as there may be difficulties and limitations, particularly among the elderly. Replacing a device cannot be allowed to lead to loss of asthma control, and the best device is always that which the patient is able to use.

Asthma control is of paramount importance for the atmosphere. Published research in the European Respiratory Journal, based on data from more than 206,000 asthma patients in the UK, has demonstrated that greenhouse gas emissions may be lower among those who are able to get their diseases under control within a year, when compared to emissions generated by patients with uncontrolled asthma. The study suggests that controlling asthma may reduce the carbon footprint per person by up to a third.

Device disposal

Urrutia-Pereira suggests other actions to reduce the carbon footprint, such as reusable inhalers, products for longer treatment (e.g., options that last 90 days), and recycling. Currently less than 1% of the world’s inhalation devices are recycled, a figure that must achieve at least 81% to eliminate all emissions associated with their disposal.

“This will require significant investments and behavioral changes,” says the UNIPAMPA lecturer. “Recycling at places such as pharmacies would enable the repurposing of plastic or aluminum components. Inadequate disposal of devices containing unused doses is of particular concern, as they continue to release gases.”

Another relatively simple guideline is that pressurized metered-dose inhalers be used once a day instead of being divided into two inhalations, as is normally prescribed.

In addition to the environment, one group of people is directly affected by the noxious effect of volatile anesthetics: teams working in surgical centers lacking exhaust systems. A study funded by the São Paulo State Research Foundation (FAPESP) was one of the first to evaluate genetic instability, cell death, and proliferative index in exfoliated buccal cells in medical anesthesiologists.

The authors, all researchers from São Paulo State University (UNESP), Botucatu Campus, also assessed damage to DNA and determined the concentrations of residues from anesthetic gases more commonly used: isoflurane, sevoflurane, desflurane, and nitrous oxide. “Workplace exposure is not associated to systemic genotoxicity but results in genome instability, cytotoxicity, and proliferative alterations in target cells (oral mucosa),” explains physician Leandro Gobbo Braz, vice coordinator of the UNESP postgraduate anesthesiology program, and one of the research authors.

Another study conducted by the same group took the innovative approach of evaluating genetic and cell markers in professionals working in veterinary surgical centers without exhaust systems. An association was found between the high levels of workplace exposure to isoflurane residues and genetic and cell alterations in anesthetists and surgeons.

“These professionals working in both human and veterinary surgical centers in Brazil may be considered as being at risk of developing genetic alterations as a result of this exposure,” warns the study’s main author Mariana Gobbo Braz, from the School of Medicine at UNESP’s Botucatu Campus.

Anesthetic gas residues in operating rooms without active exhaust systems have been associated with adverse health effects. Concentrations of isoflurane and sevoflurane in surgical spaces analyzed by the UNESP research team were higher in relation to the recommended limit, which is 2 parts per million.

Ensuring that operating rooms have adequate exhaust systems is one of the explicit recommendations in the action guidelines from the US and Australian researchers to deal with pollution caused by inhalational anesthetics. Efficiency in this matter serves to reduce both environmental contamination and exposure of professionals.

*

This article may be republished online under the CC-BY-NC-ND Creative Commons license.

The text must not be edited and the author(s) and source (Science Arena) must be credited.